Rigged For Reform

Three years after a sharp fall in global energy prices, Trinidad and Tobago must enact critical reforms and confront threats to economic recovery

Spurred by increased natural gas production and a rebound in international commodity prices, the modest economic recovery which began in 2017 in Trinidad and Tobago continued in earnest through 2018. But a year on, it’s still far too risky to celebrate.

According to the Central Bank’s 2018 Financial Stability Report, a sharp, sudden fall in the price of oil or gas could create liquidity and solvency issues for local financial institutions and make it difficult for the country to meet its debt obligations.

That’s not the only potential complication.

The latest report from the Trinidad and Tobago Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (available below) points to a set of vulnerabilities within the oil, gas and mining sectors which could hamper any real chance of sustained economic growth or, worse, open the floodgate to corruption or environmental incidents.

These are crucial issues which, while not new to people working in these industries, must be addressed in profound ways for the sake of ordinary citizens who may not fully understand them.

Ordinary citizens who—make no mistake about it—are the real owners of T&T’s oil, gas and mineral resources, and on whose behalf the TTEITI has been working to promote open and accountable management by extractive companies.

Take recent developments concerning the exploration and production of hydrocarbons…

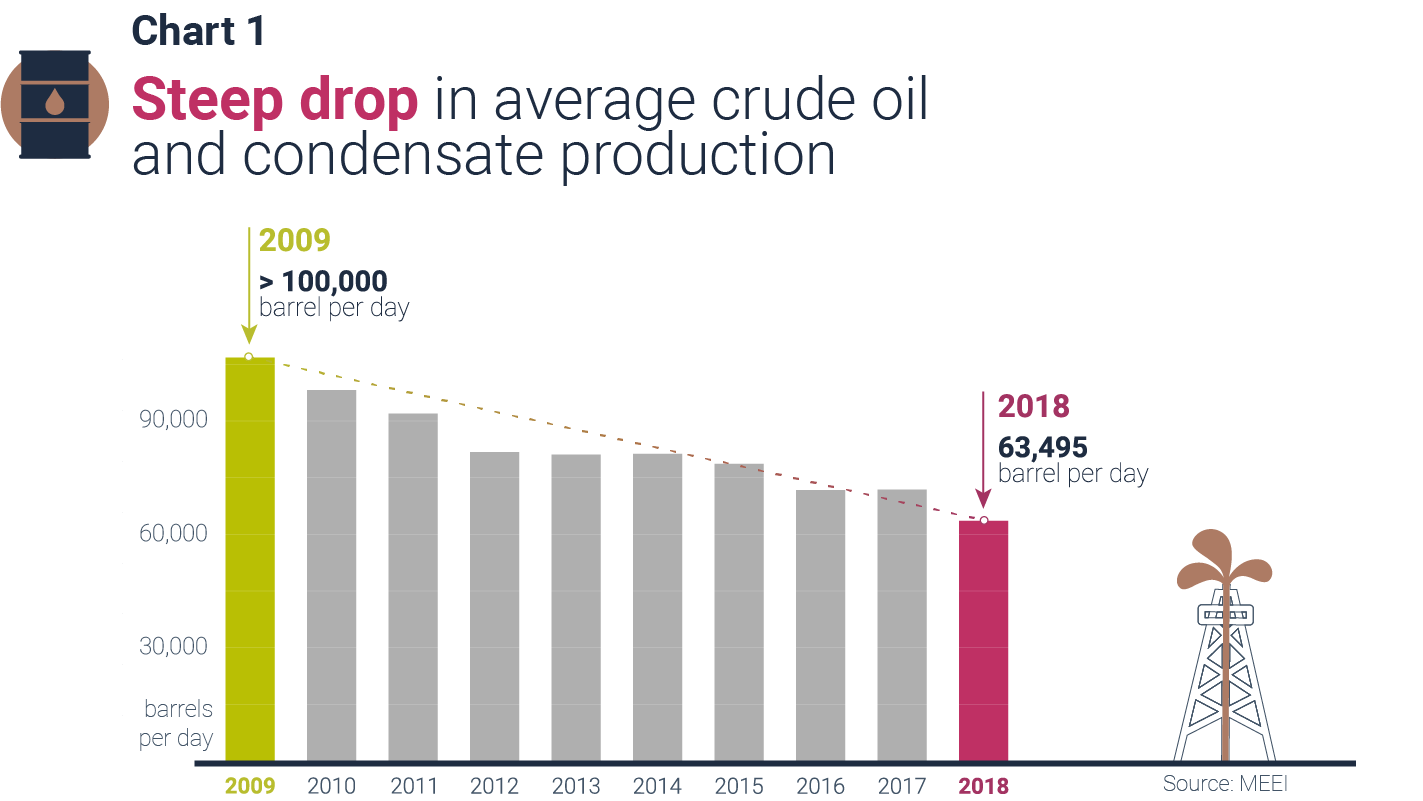

While 2017 saw a slight uptick, average crude oil and condensate production fell to an annual average of 63,495 barrels per day in 2018, a steep drop-off from the more than 100,000 barrels produced in 2009, and not least because T&T’s oilfields have matured since the first well was drilled over 100 years ago.

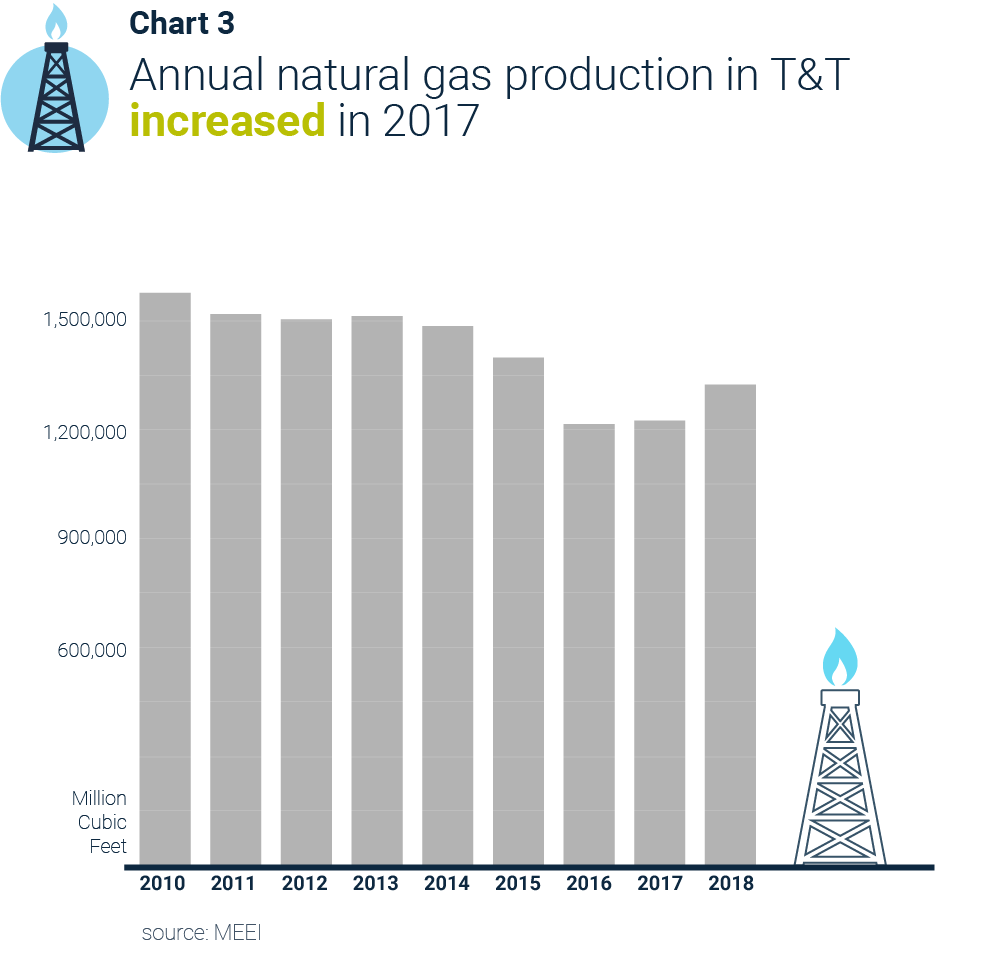

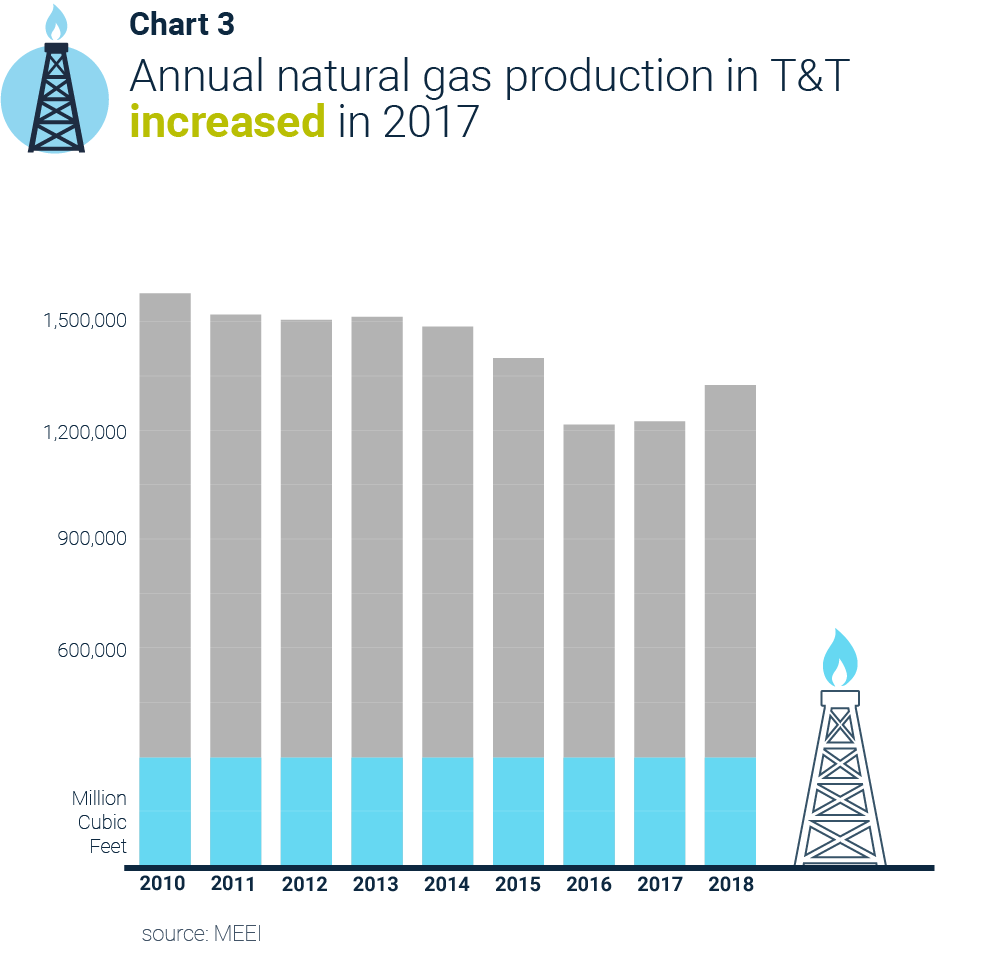

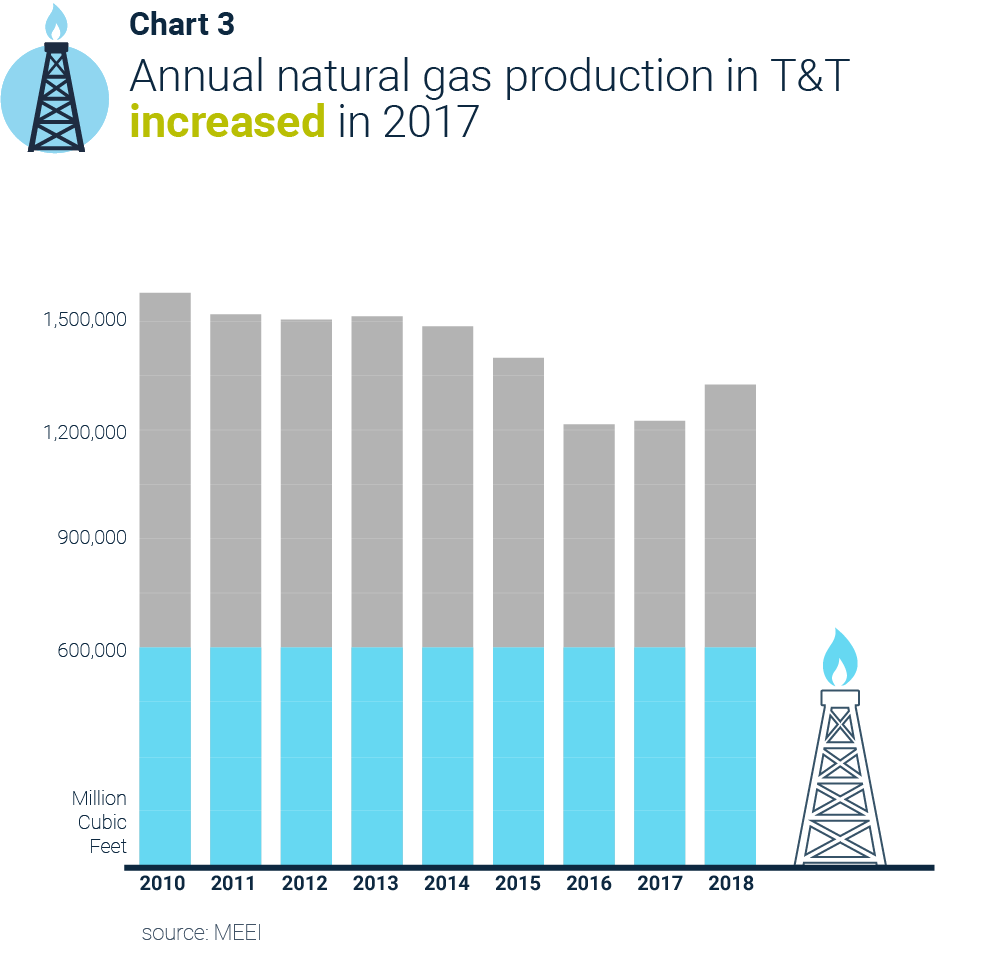

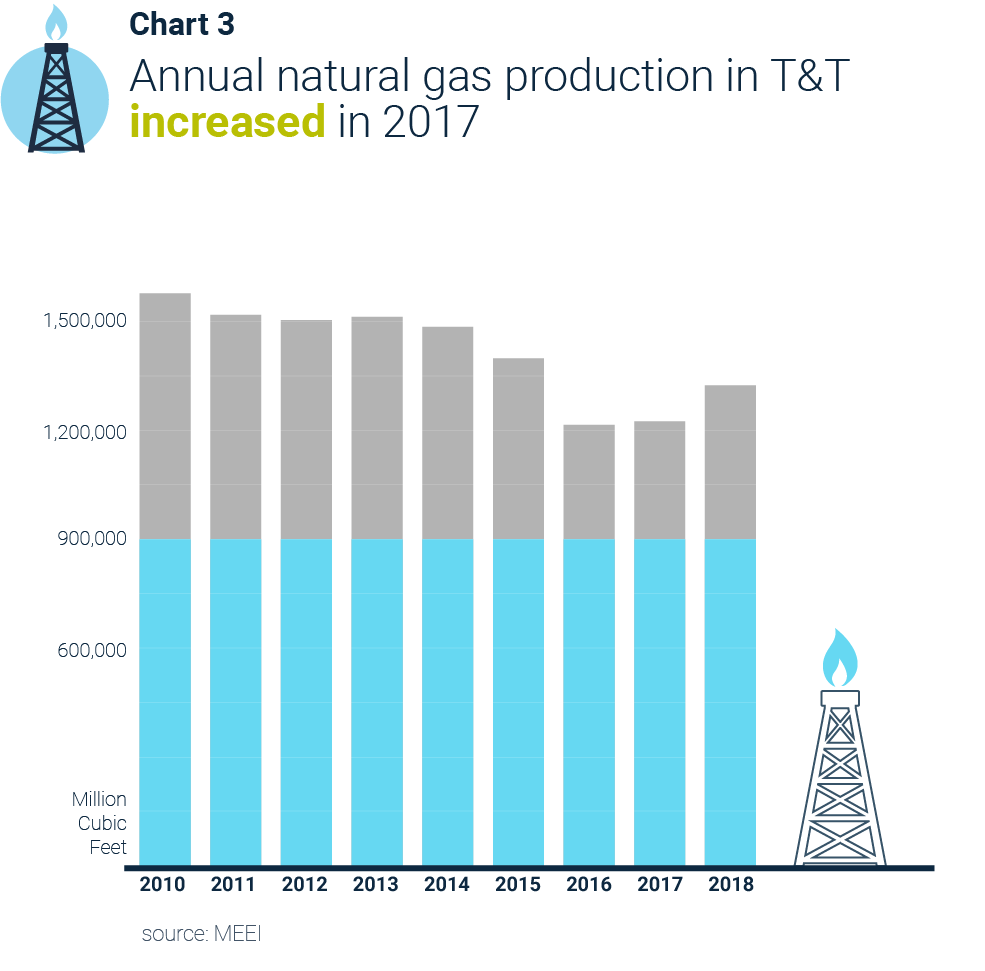

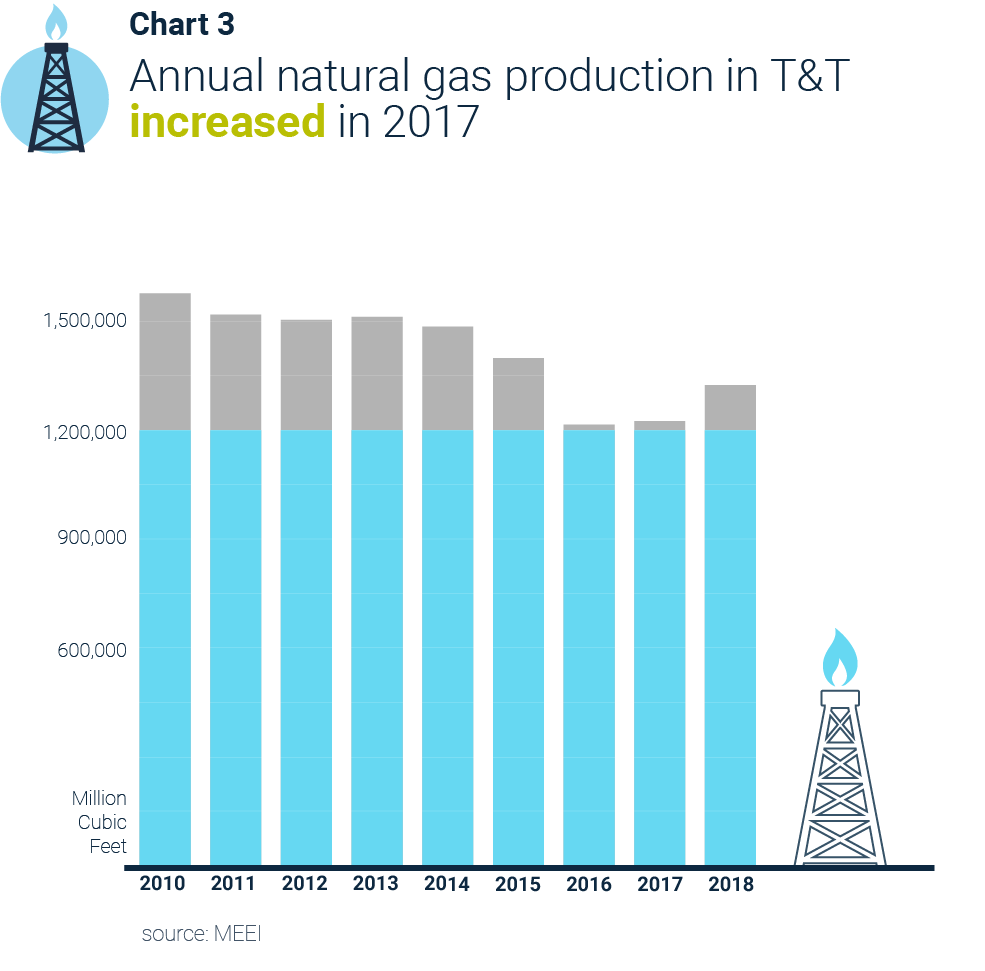

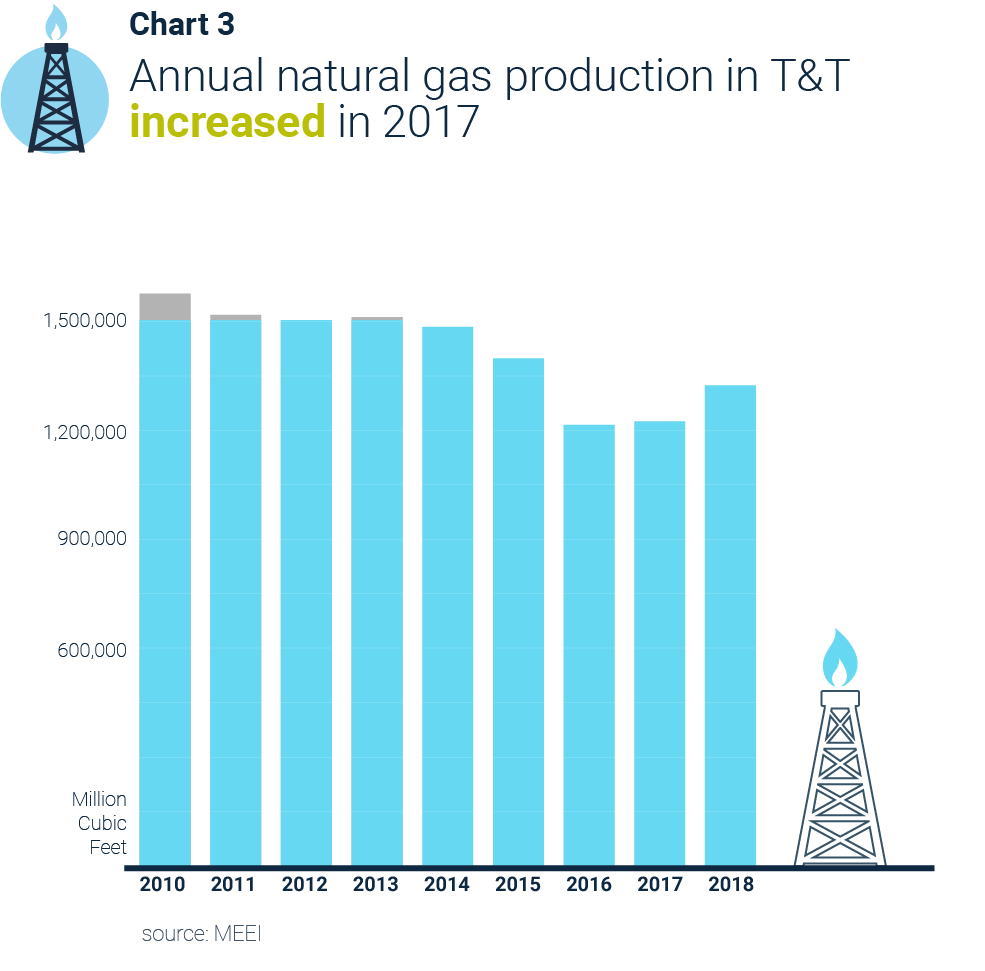

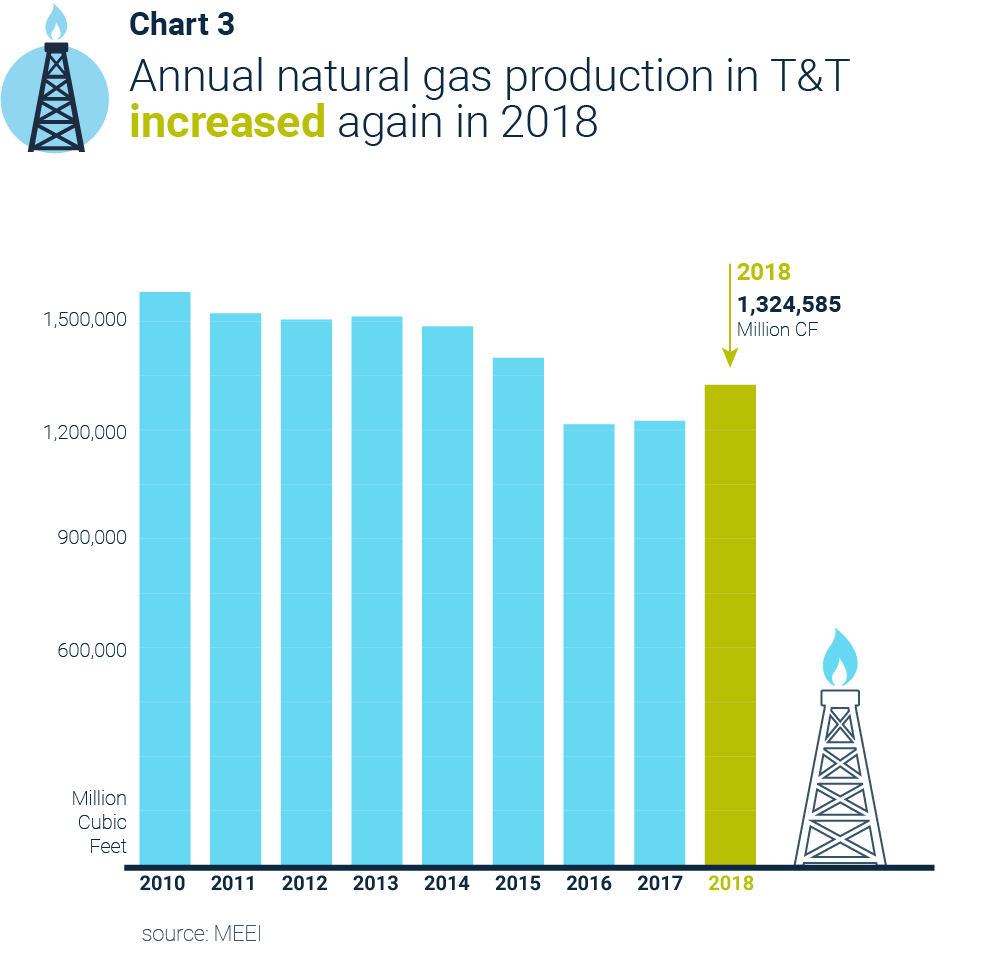

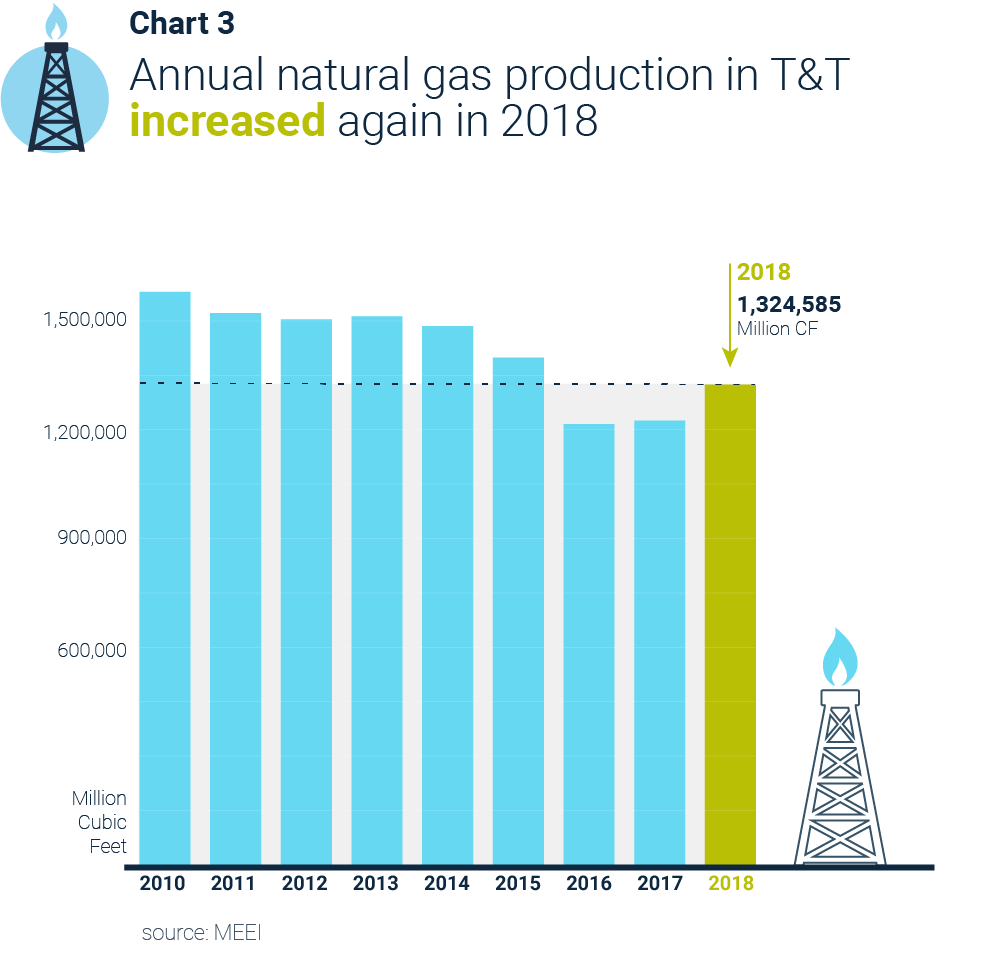

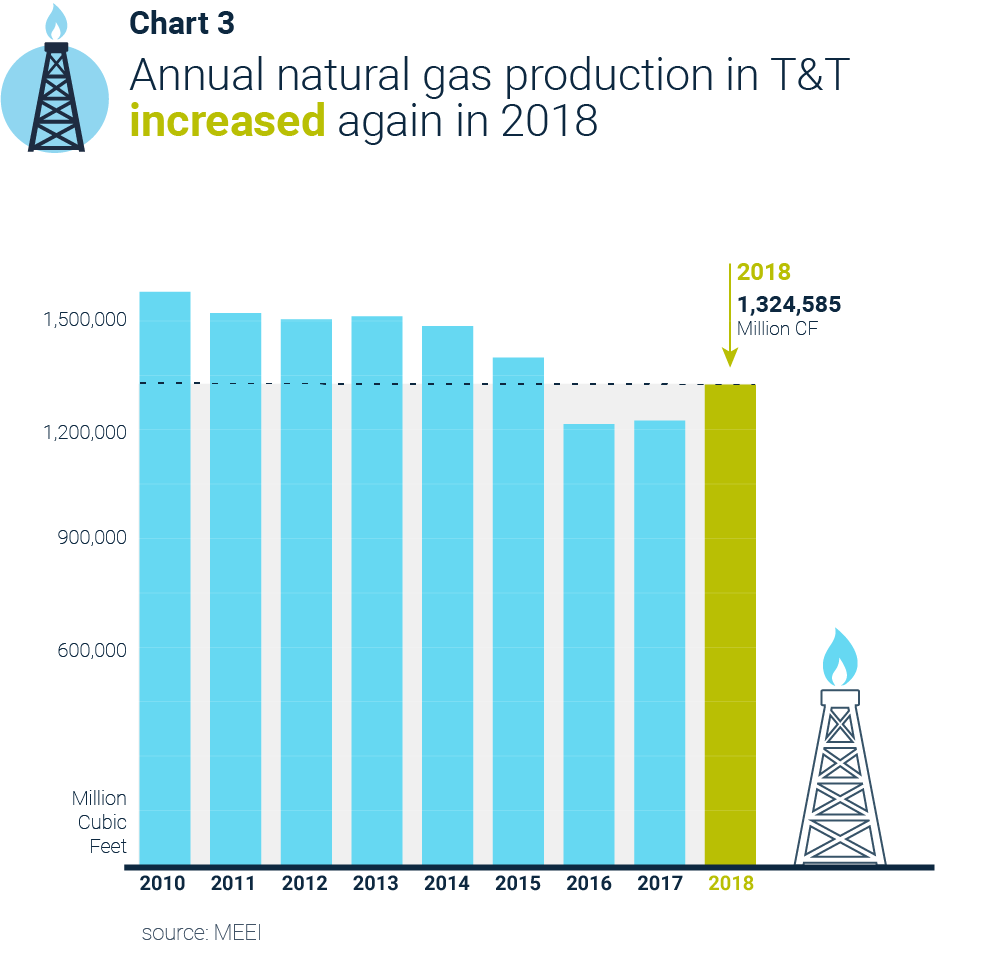

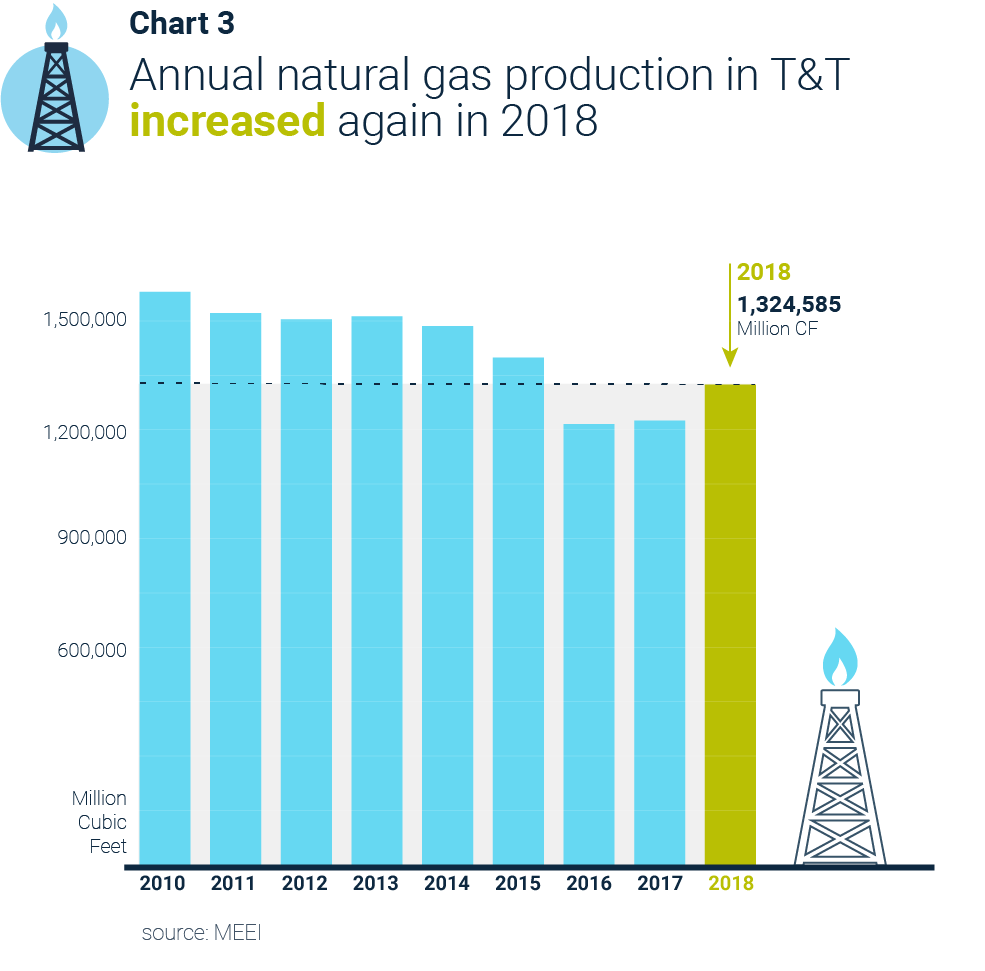

Natural gas production also decreased steadily between 2010 and 2016, from 4,330 million standard cubic feet of gas a day (mmscf/d) to 3,330 million standard cubic feet a day.

And then a ray of sunshine: A marginal increase in 2017 that continued in 2018 with gas production averaging 3,629 million standard cubic feet a day according to the Ministry of Energy’s Consolidated Monthly Bulletin.

It was a positive development which had its roots in efforts by the government going back a few years to inspire exploration activity by upstream operators.

BHP Billiton, Lease Operators Limited and BPTT drilled nine wells between 2017 and 2018. The government did its part, inviting exploration and production bids for six offshore shallow-water blocks located off Trinidad’s eastern, northern and western coasts.

By November 2018, DeNovo’s Iguana field was producing 80 million standard cubic feet of gas per day. Then even more good news: BPTT’s Angelin project, located 60 kilometres off the south-east coast of Trinidad, delivered its first gas in the first quarter of 2019.

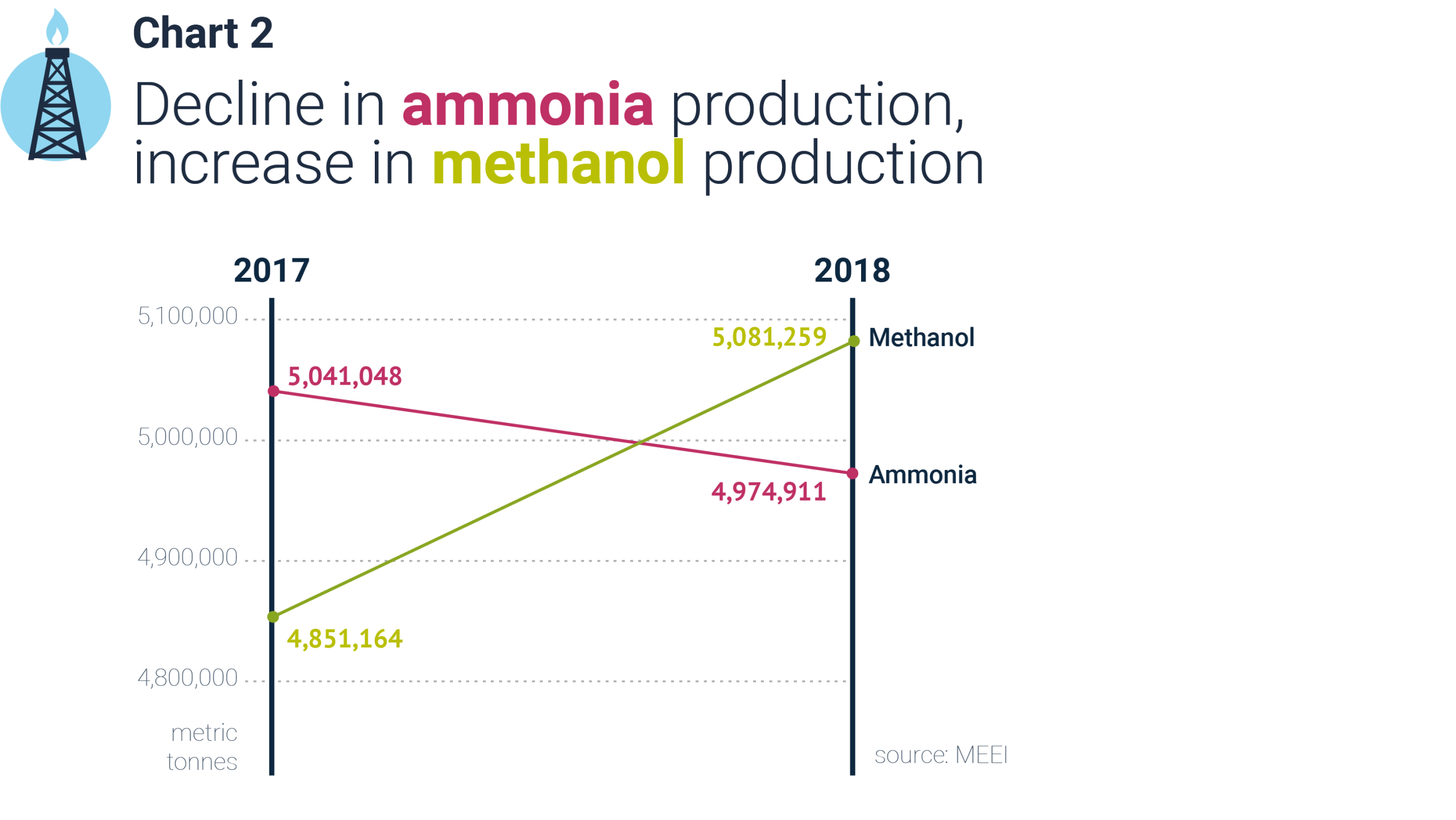

Meanwhile, petrochemical production experienced its own challenges. Four of the six methanol plants in the country reported a decline in production in 2018, but there was a 2 percent increase between 2017 and 2018 at the M4 and Titan plants which pushed numbers up overall.

On the other hand, through 2018, ammonia production fell far short of production targets declining 1.3 percent from 5,041,049 metric tonnes in 2017 to 4,974,911 metric tonnes in 2018.

These developments raise an important question…

If current production levels for oil, gas and petrochemicals hold what will that mean for Trinidad and Tobago’s economy?

Fresh Concerns Over Flawed Production Data

Trinidad and Tobago will face a revenue shortfall through 2020 if current production levels dip, and the situation could be dramatically worse if there is a global decline in commodity prices.

Recent developments like the Dragon Field gas deal between the government and Venezuela and BPTT’s plan to tap low-pressure gas reserves from fields in the Greater Cassia Area suggest the country is taking important steps to meet its targets. But the fact remains that it is currently producing much less than it needs.

One major reason for the production stalemate is the routine and costly shutdown of natural gas facilities for maintenance work. Case in point, the decline in ammonia production in 2018 could be directly traced to disruption in natural gas supply caused by plant repairs.

Atlantic LNG, the country’s largest user of natural gas, has been particularly hard hit.

True, recent investments in new exploration and production programmes may boost production and revenues in the short term. But to improve the long-term outlook for growth, the country must pursue other important reforms. Key among them is addressing flaws in quantifying oil, gas and mineral production.

In a contribution to the TTEITI’s latest report, the auditor general identified several gaps in how the production data submitted by upstream oil and gas companies is verified.

For one thing, there is no collaboration between the people who review monthly production reports—the contract management unit at the Ministry of Energy & Energy Industries—and those who are responsible for approving and calibrating the measurement systems which produce the data these monthly reports refer to.

The auditor general suggests this measurement unit may be constrained on two fronts: a lack of training and a severe shortage of manpower.

If, for example, employees of the contract management unit raise questions about specific production reports, their colleagues in the measurement unit don’t even have the wherewithal to log the queries far less review the data.

How does this inefficiency impact the accuracy of oil and gas production data? If the production data is off, doesn’t it create the possibility that market values being bandied about for the country’s oil, gas and petrochemical assets could be wrong? And doesn’t this potentially lead to lower tax revenues for the government to do its work?

One major reason for the production stalemate is the routine and costly shutdown of natural gas facilities for maintenance work.

The case is further strengthened by back-to-back reports from the auditor general which are anything but contradictory.

“The accuracy of revenue from royalties and share of profits from oil companies,” he writes in his 2016 report, “could not be assessed.”

The following year, the auditor general again reported that “Examination of the Draft Strategic Plan that was sent to Cabinet for approval revealed that the Ministry of Energy & Energy Industries did not address the weaknesses related to the ministry’s inability to determine the veracity of production data...”

There’s been a few positive developments since. Concerns over the accuracy of oil and gas production data has gained renewed traction within the ministry which is compiling a preliminary report on production verification processes in other countries as a first step to address the gaps in its own system.

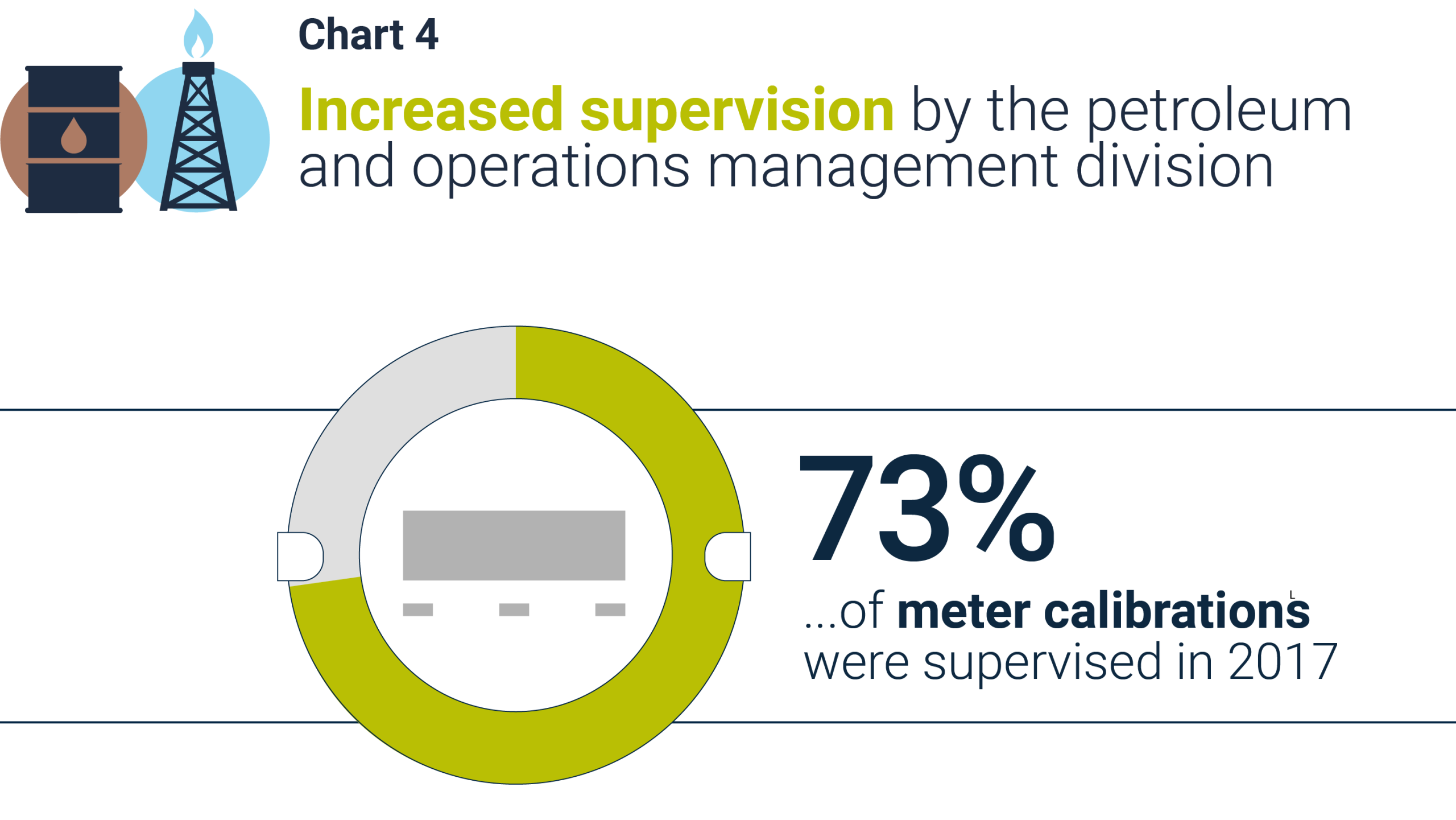

Additionally, the petroleum and operations management division which is charged with monitoring and witnessing petroleum management activities reported an improvement in the total number of meter calibrations they supervised—as much as 73% in 2017.

Nevertheless, given the sector’s strategic importance to Trinidad and Tobago’s annual budget, policy makers must move quickly to create confidence around the production accounting methodology.

To do otherwise will be costly.

In fact, the country is already losing untold millions considering the challenges it’s facing in analysing mineral production volumes.

The case of andesite, the main rock mineral quarried on the island of Tobago, underscores the problem because for many years no data has been reported for andesite extraction.

Explanations from the regulator abound: Quarterly reports on mineral production are completed three to six months late. Delinquent operators slow the reporting process. No single officer is assigned to compile the data on royalties and production.

There is also the reality of no single market value of mineral production because there is no benchmark price of minerals sold on the local market. Even at Lake Asphalt, one of the country’s largest quarry operators, updated price and production data are not available.

The Ministry of Energy has taken concrete steps to remedy the situation by hiring new staff. Yet probe a bit deeper and the situation around mineral extraction in Trinidad and Tobago is so dire it would take new policy—not just additional personnel—to solve it.

The open secret in this twin-island Republic is that problems in the mining sector aren’t simply about the lack of proper regulation and oversight around production data.

It’s about the calculated exploitation of the country’s mineral resources by some unscrupulous operators who capitalise on lax regulation and rob the government of much needed tax revenue on a grand scale.

Mining Operators Extract Wealth, Skip Royalty Payments

With the plunge in global commodity prices deflating tax revenues from oil, gas and petrochemicals, Trinidad and Tobago could shore up income from its mineral resources. But the industry is plagued by a host of problems including a significant issue of tax leakage.

In 2018, quarry operators owed the government TT$201 million in royalties. Just over $21 million was paid. Approximately $174 million in tax receipts went uncollected, an opportunity to redistribute mineral wealth belonging to Trinidad and Tobago citizens fading into broader concerns about mismanagement and corruption.

The mining sector here is dominated by a slate of state‐owned and locally-owned private companies who file reports on the volume of minerals they extract from data they put together themselves. But how does the government verify the data provided by these operators?

Ministry officials say they are looking into drone technology to independently verify production data and hold operators accountable and in 2018 made an important step to invite expressions of interest for the programme.

But one prudent observer, no less than the auditor general, concluded in a 2017 report that “production data that was submitted by the [mining] extraction companies was not examined by the ministry with a view of determining the accuracy of the data submitted.”

To put it plainly, much-needed royalty payments remain uncollected simply because of under-reporting by quarry operators and the regulator’s inadequate systems. But more than that, this situation puts both the government and reporting companies in breach of EITI Requirement 4 which calls for comprehensive disclosure of taxes and revenues by oil, gas and mining companies which are subject to credible, independent audit according to international standards.

In the decades of plenty, $174 million in unpaid royalties would be unacceptable. How much more now with the economy still brittle following the fall in the price of commodities a few years ago?

Compounding the issue, there are several unlicensed operators making good on the economic opportunities Trinidad’s mining sector offers but well outside the scope of environmental regulations and indeed the law.

While some unlicensed operators pay royalties, they are not required to do so based on current legislation. The Ministry of Energy has been slow to clamp down. After many years, enforcement of the Minerals Act of 2000 remains weak even as environmental risks soar.

Little surprise, then, that one of the largest quarry operators in the country, National Quarries Limited, is state-owned but unlicensed.

The ministry puts the total number of licensed quarry operators at eight. Official word is that the government is looking to increase staff at the minerals division to help address some of the issues. There is also talk of an electronic licensing management system which will apparently work in tandem with the drone system to remedy the production data problem.

From the TTEITI’s vantage, the time has come for the ministry to impose strict deadlines for correcting this issue of licenses and permits.

It must happen before the next report is published.

The ministry must also expedite procurement of drone technology, already in use in the private sector, to better monitor mineral production so that royalties could be assessed and collected. A hundred and seventy-four million may seem small now but that figure could be amplified overnight by shocks originating in the international energy market.

Tax avoidance by mining operators is but one issue surrounding revenue collection from Trinidad and Tobago’s extractive companies.

Worth mentioning also is the challenge with collecting revenue from production sharing contracts in which the government has a stake.

Audits for the period 2014-2017 identified US$487,000 in under-reported revenue. By the end of 2018, the government still had not recovered this sum.

The same audits showed that US$88 million in costs had to be permanently disallowed, which is to say, they revealed that extractive companies were not entitled to tax allowances in this amount due to inconsistencies in production costs.

In the decades of plenty, $174 million in unpaid royalties would be unacceptable. How much more now with the economy still brittle following the fall in the price of commodities a few years ago?

These audits have a big job. In a very real way, they help to ensure companies earn the tax concessions they are entitled to. When there is a lag in the audits, government share of revenue is threatened since this is the official method by which the state confirms the correct revenue it is entitled to from its production sharing contracts.

And here, again, there are challenges with data since some ministry records are in the form of spreadsheets which are prone to inconsistencies.

As a result, the TTEITI has stressed the need for the introduction of appropriate computerised systems before plans to mainstream industry information materialise.

There is, after all, a direct connection between how the ministry manages data and the amount of revenue the state collects. That’s the nub of the matter.

Overhaul of Sovereign Fund Could Boost Economic Fortunes

The oil and gas industry in Trinidad and Tobago is notorious for dramatic booms and busts going back decades. The sector doesn’t employ a lot of people but it posts a sizeable contribution to the annual budget and is the main driver of the country’s sovereign wealth fund known as the Heritage and Stabilisation Fund (HSF).

According to its governing legislation, the purpose of the HSF is two-fold: Save and invest surplus petroleum revenues to support domestic spending during periods of economic downturn. And provide for the economic well-being of future generations of Trinidad and Tobago citizens.

Under the legislation, petroleum revenues are placed in the HSF in each quarter of the financial year if the revenues for that quarter exceed budgeted revenues by more than 10 percent.

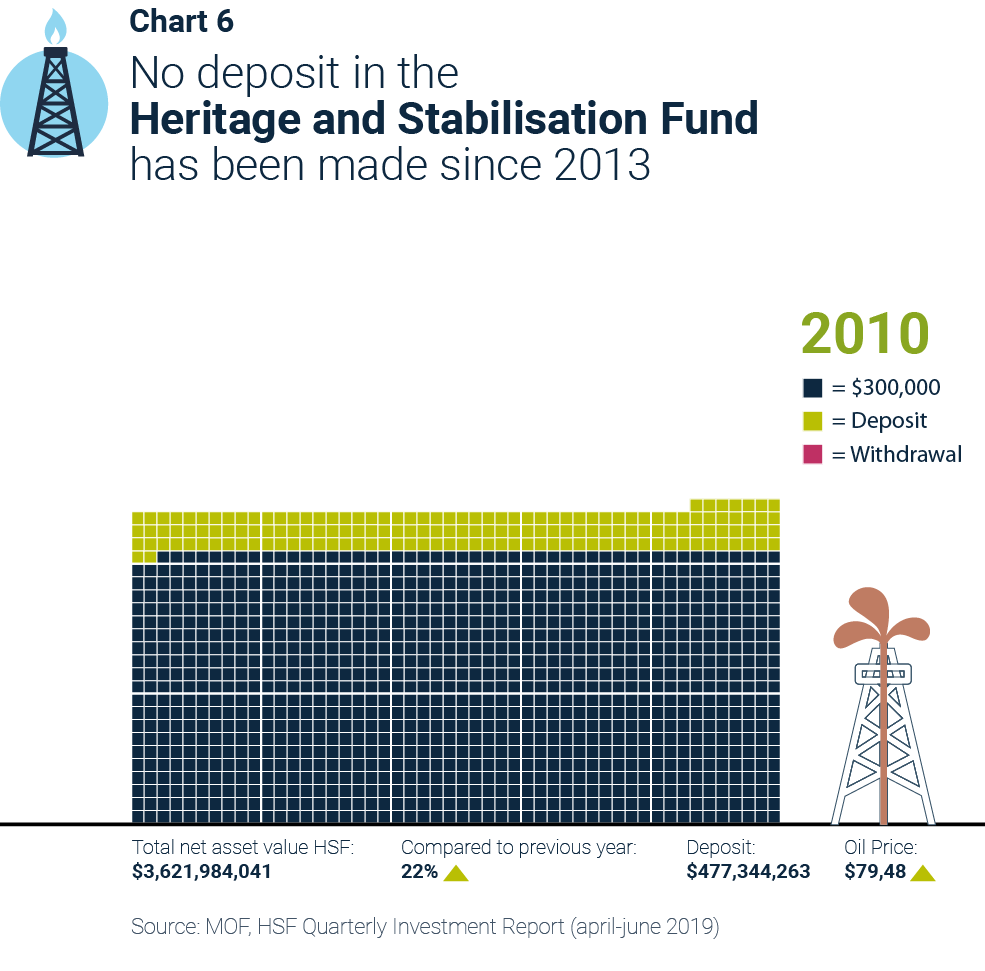

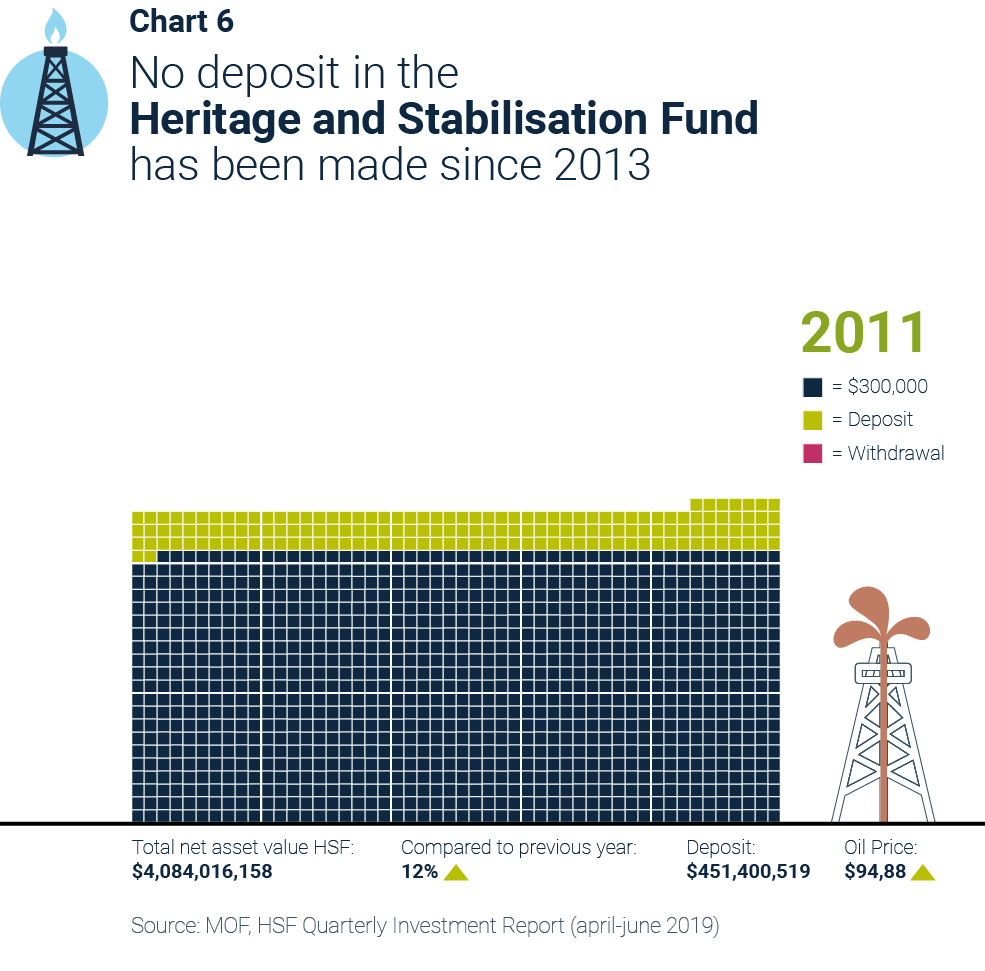

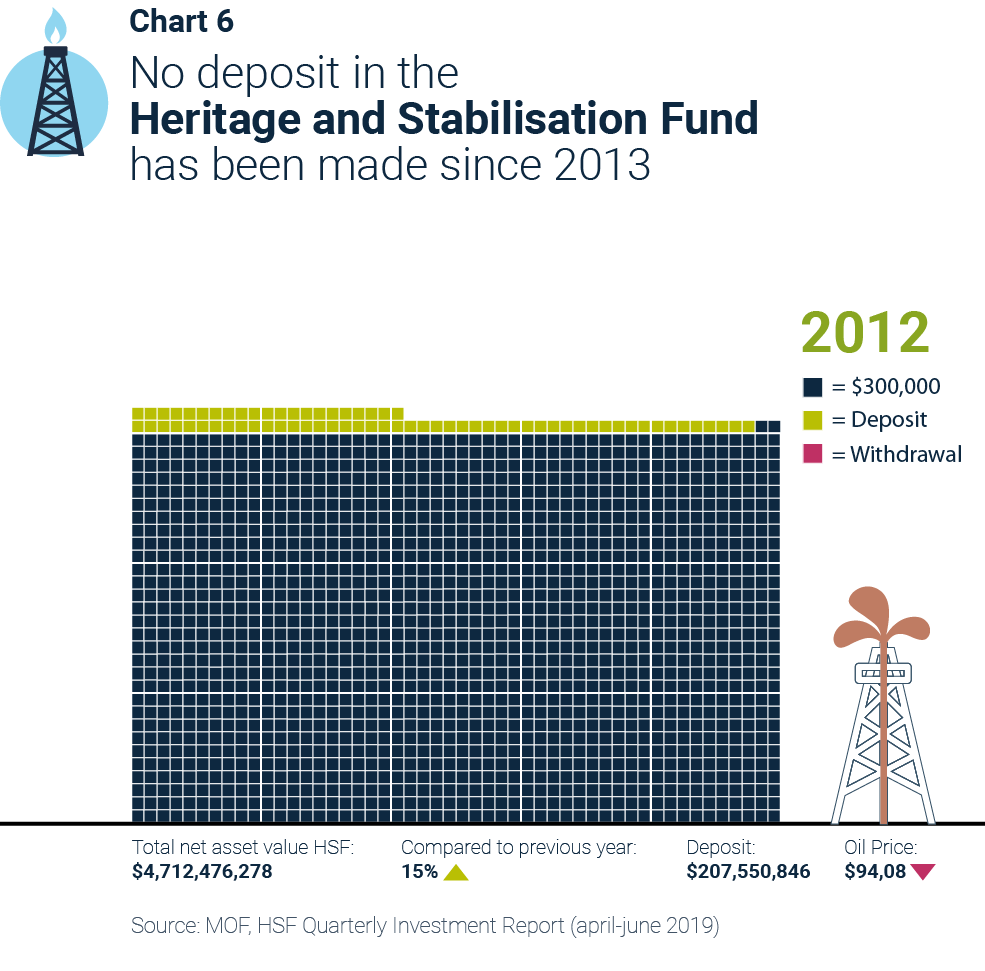

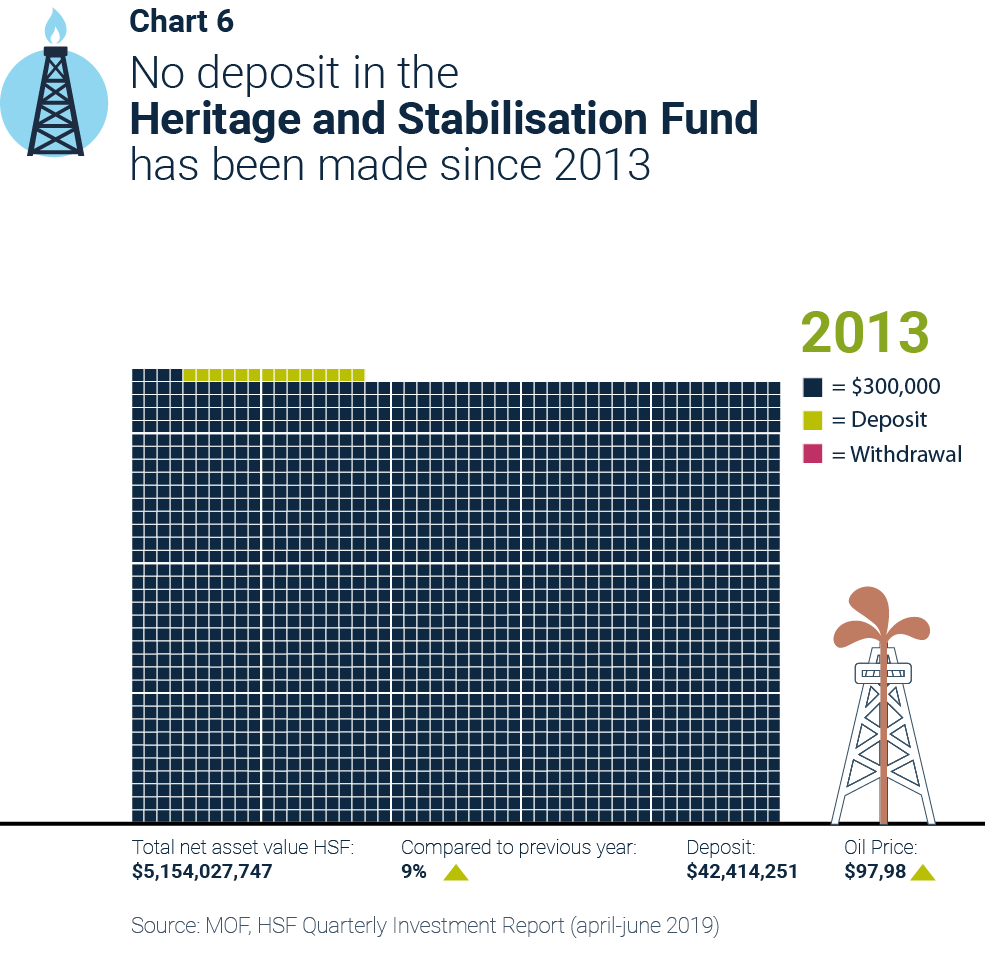

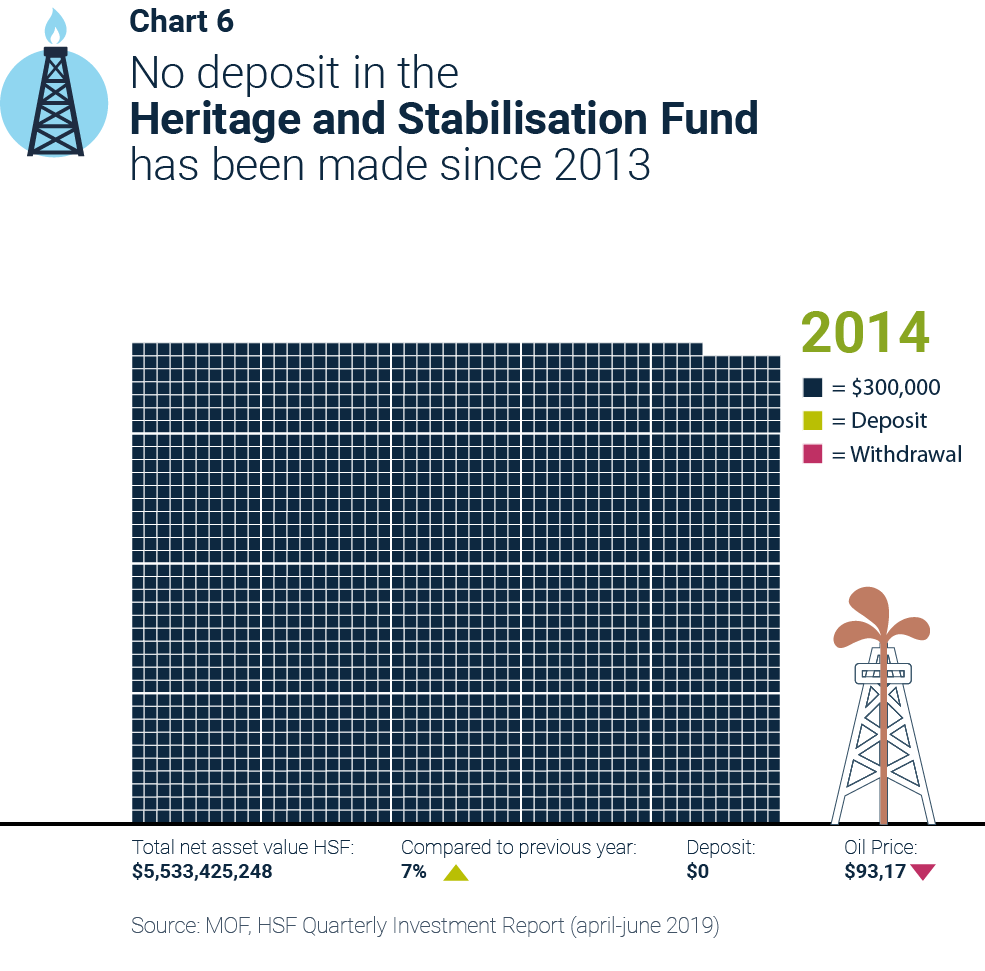

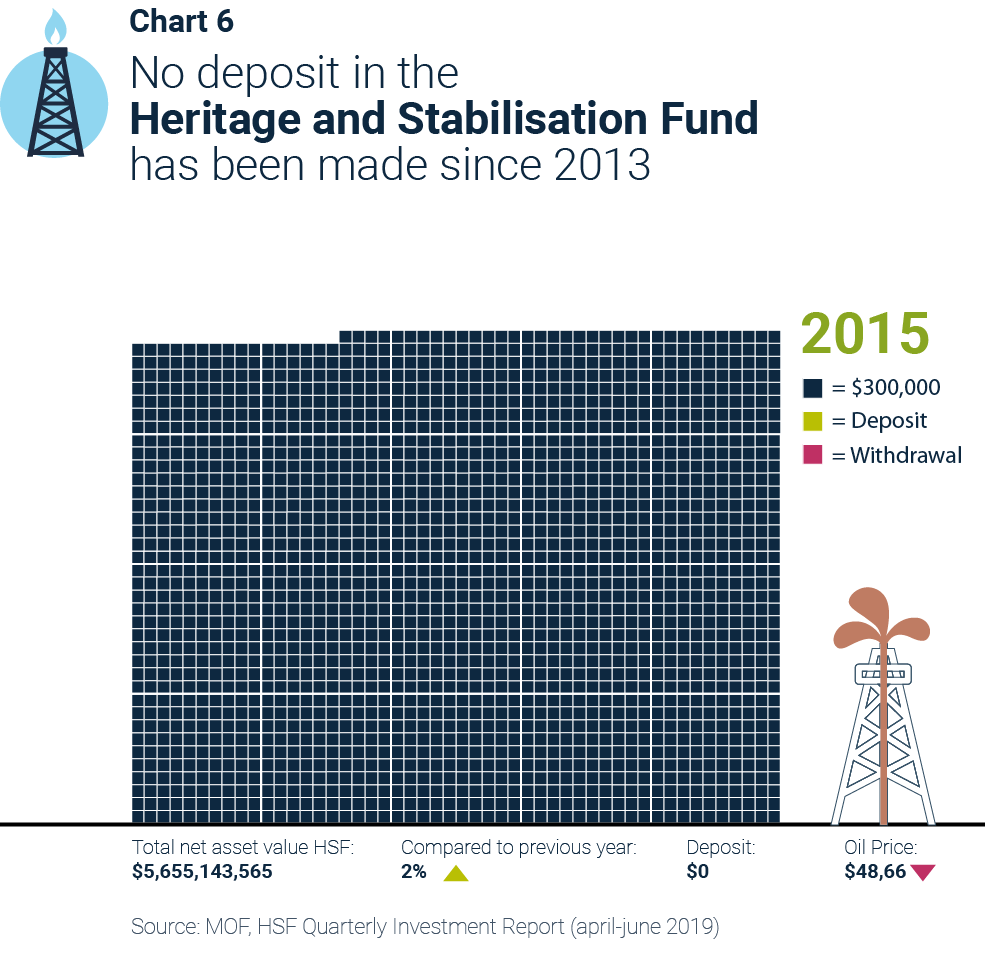

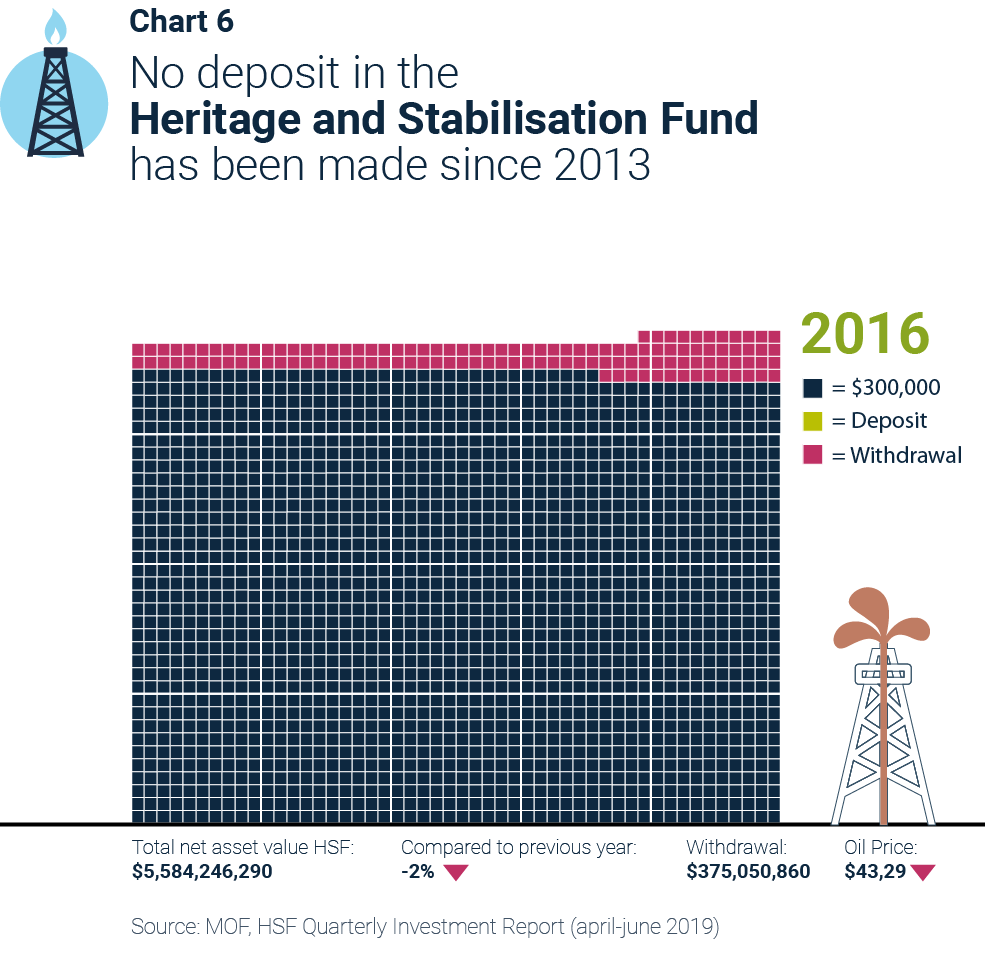

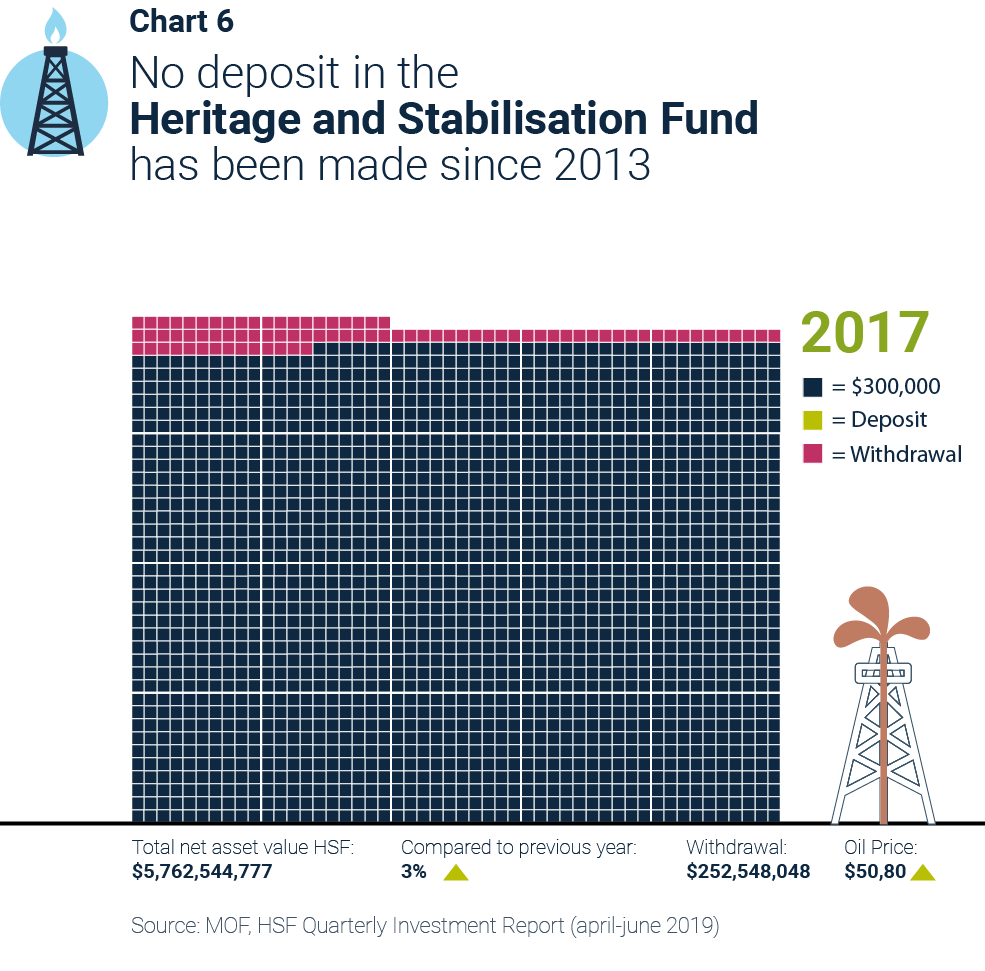

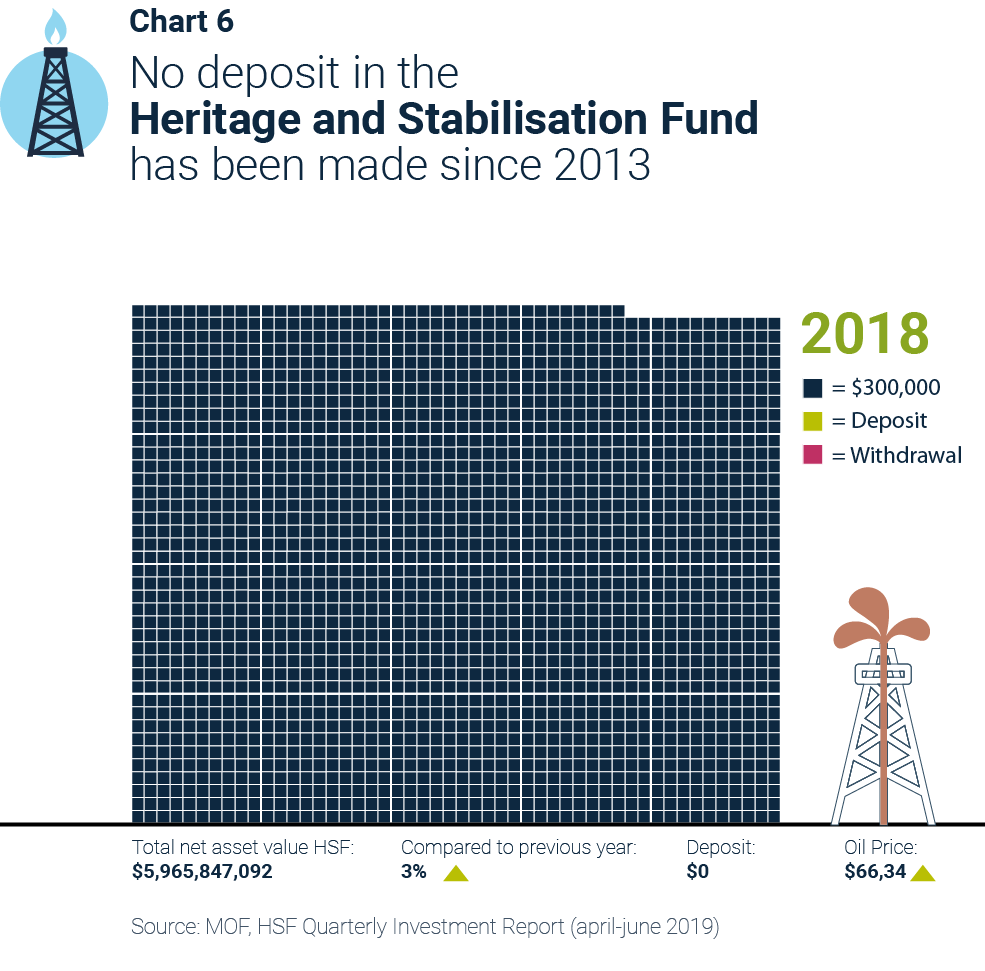

But consider the net effect of this rule when the price of oil falls: Since 2013, there have been no deposits into the HSF raising concerns that current fund rules potentially endanger future prosperity.

It’s one reason HSF reform is a central pillar of the TTEITI’s latest report, and it follows decisions taken by Trinidad and Tobago’s Finance Minister Colm Imbert to draw down the HSF by TT$2.5 billion in 2016 and TT$1.7 billion in 2017 both times to boost domestic spending.

Prime Minister Keith Rowley seems to be in step with sentiments expressed by some local commentators and analysts to restructure the HSF, announcing in 2017 that his government had retained an expert to put concrete proposals on the table.

But that was two years ago.

As a matter of economics, there is merit in rethinking the HSF and addressing three major issues with its current structure, starting with the need to protect its heritage function.

This will likely mean breaking up the HSF into two separate funds and amending the existing legislation to safeguard the heritage fund for generations to come, a growing consensus particularly among stakeholders from civil society groups.

Following the withdrawal of US$637 million, their concerns aren't simply about the government’s decision to use HSF funds. Rather, it's about the decision to use the money for recurrent expenditure especially in cases where no compelling cost-benefit analysis has been provided to the public.

Perhaps the time has come for policy makers to consider recommendations to spend only the interest component of the heritage portion of the fund and to use this money primarily for capital projects like hospitals, roads, and schools. This is one way to preserve the heritage intent of the HSF while ensuring the public has a perception that the fund is being properly managed.

As a next step, another significant amendment is the basis on which deposits are made into the HSF in the first place. Right now deposits are based solely on revenues accrued under the Petroleum Taxes Act. But these deposits do not include midstream and downstream revenues from petrochemical companies or other profitable players like the National Gas Company.

Under these rules and indeed the law, commodity prices could be high and no deposits would be made in Trinidad and Tobago’s sovereign wealth fund, a situation which, in the view of the TTEITI, is antithetical to ‘rainy-day’ wealth accumulation.

The price of oil averaged US$95 a barrel between 2011 and 2014, a striking recovery from 2010 when it had fallen to US$79.48. Yet the net value of HSF deposits fell sharply, from US$451,400,519 in 2011 to US$42,414,251 in 2013. In 2014, with the price of oil holding steady at over US$93, no deposit was made into the HSF.

And none since.

Still, considering the temperamental markets, the HSF hasn’t performed badly. Not even close. At the end of September 2019, the net asset value of the fund was US$6.25 billion, but the question is…

What would the value have been if Trinidad and Tobago had committed to making consistent deposits into the fund by tapping the revenues of petrochemical companies?

Conclusion

The extractive sectors are at once a blessing to Trinidad and Tobago and a challenge for its government. On the one hand, public scrutiny and EITI requirements demand holding extractive companies accountable albeit under a voluntary EITI system.

On the other hand, the government must play the role of facilitator providing incentives to get optimal production out of these same companies. For what is production if not another word for profit.

In this article, we advocated for critical reforms in policy and practice across Trinidad and Tobago’s oil, gas and mining sectors. Taken together, they set the tone for sustained economic recovery and, in so doing, help to ensure T&T citizens benefit from the exploitation of their country’s natural resources.

Our recommendations call for radical collaboration among stakeholders and new, improved systems at the Ministry of Energy. In some cases, the potential fix is as simple as increasing staffing in key departments like the minerals division.

In others, the government should embrace the idea of a comprehensive rethink of governing policy, as in the case of the Heritage and Stabilisation Fund which protects future generations. And because of significant tax leakage, the mining sector presents its own unique challenges which the government needs to overcome.

This work is both doable and necessary.

What would the value have been if Trinidad and Tobago had committed to making consistent deposits into the fund by tapping the revenues of petrochemical companies?

Leading economists agree that despite the recent uptick in commodity prices revenue dangers loom heavily over the T&T’s economy. Making progress in areas like production, revenue collection and revenue allocation helps to mitigate these risks.

And crucially, new requirements under the 2019 EITI Standard broaden the scope of risks the country faces in oil, gas and mining to include the environment and contract transparency, both of which the TTEITI will speak to in its next annual report.

When it comes to environmental issues, it’s not just about what extractive companies are doing to treat with here-and-now dangers like oil spills. The EITI goes further, calling for implementing countries like Trinidad and Tobago “to disclose information on the management and monitoring of the environmental impact of the extractive industries,” including relevant legal provisions and administrative rules as well as actual practice related to environmental management and monitoring.

We must also reconsider the terms and conditions of all contracts and the lack of transparency around them. Currently, governing law doesn’t support contract transparency but would Trinidad and Tobago citizens get better value from their resources if they knew the exact terms of these contracts?

Would market value calculations published by the Ministry of Energy square with agreements between the government and the extractive companies if contracts were exposed? Or would issues related to transfer pricing and loss of revenue have been raised earlier if analysts had access to contracts and were able to spot inconsistencies?

Effective Jan. 2021, the EITI Standard will require implementing countries “to publicly disclose any contracts and licenses that provide the terms attached to the exploitation of oil, gas and minerals.”

At stake is the socioeconomic well-being of Trinidad and Tobago citizens who depend on the wealth created by these natural resources and whose interests are served by how carefully and transparently we manage them.

About the TTEITI

In Trinidad and Tobago, extractive industries refer to those industries engaged in exploring for and producing oil, gas and minerals. The Trinidad and Tobago Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (TTEITI) is the local arm of a voluntary global initiative that promotes transparency and accountability in the oil, gas and mining sectors. We are not a government-led entity. Rather, various stakeholders from civil society, extractive sector companies and the government collaborate on our Board/ Steering Committee to ensure that country’s natural resources are used to the benefit of all citizens.

Research: Nazera Abdul-Haqq

Additional research: Sherwin Long, Gabrielle Rawlins, Diandra Grandison

Writer and editor: Kerry Peters

Data visualisation: Hilje de Boer

Design and development: Yellow House Media

Photos courtesy: Energy Chamber of Trinidad & Tobago

This article is based on the facts and figures contained in the 2017 TTEITI Report. Click the button or cover to download the full PDF version.

Download a PDF version of the TTEITI's latest report

Download a PDF version of the TTEITI's latest report