A Guide to the

Trinidad and Tobago

Budget for Civil Society

Organisations

CSOs must play a larger role in public finance

Sponsored by the US Embassy

Sponsored by the US Embassy

Introduction

Transparency in budgeting allows citizens and civil society organisations to see how public money is gathered and spent. While it’s a good start, transparency on its own is not enough. Engagement from civil society and a process that allows Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) to give effective input into budget planning ensures that government hears from all sectors of society, addresses actual needs, and is held accountable.

Budget decisions affect everyday life, from taxes paid by individuals, small businesses, and corporations to the services and programmes citizens use. The budget is health care for Grandma. It’s the road you take to work every day, or during the pandemic, it’s access to the internet so you can work remotely. It’s what ensures children get nutritious meals.

Those budget numbers can make all the difference in how you serve your community, clients, or members. Analysing the budget can provide ideas and information for academic studies, or be the catalyst for a news story. Understanding the budgeting steps gives you the information you need to submit a funding proposal.

The government is spending money that belongs to the public, so the public should have input into its use. This doesn’t mean CSOs will always be in agreement. Debate, conflict, and trade-offs are always present, simply because there are a variety of interests and different circumstances across communities and individuals.

The point is that as long as government is listening to civil society and working for the needs of citizens and not for itself, then we are headed in the right direction, even if there is still much work to be done. A critical first step toward participation is to teach civil society how the budget works and how CSOs can take part in the process. If CSOs want to play a role in decisions about how public money is spent, they must first understand the technical and practical functioning of the budget process.

Is this guide for you?

This guide is intended to help civil society organisations such as community-based organisations, academia, legal experts, journalists, lobby groups and local business trade organisations, find and understand the information within the national budget that is relevant to them. By analysing the information we can better monitor critical issues, participate in public policy discussions, and increase government accountability. Here’s what’s inside:

- The open budget survey and where T&T stands

- How Civil Society Organisations can benefit from deeper engagement with the national budget

- Budget timeline and processes

- Government policies and priorities

- How revenues and expenditures work

- How to read the budget as a CSO

- Suggested improvements to the budget process

- How CSOs can get involved

Open (Transparent) Budgets

Public engagement means that governments get input from those who will be affected by policy. An open (transparent) budget allows everyone to see how entities are taxed, how much debt is being acquired, and which services are being provided.

A transparent budget, processes in place for the public to participate, and a readiness for engagement from the public mean more people get what they need. It means real change for the better in terms of quality of life.

What is the Open Budget Survey?

The Open Budget Survey (OBS) is the world’s only independent, comparative and fact-based research instrument that uses internationally accepted criteria to assess public access to central government budget information; formal opportunities for the public to participate in the national budget process; and the role of budget oversight institutions such as the legislature and auditor in the budget process.

Where Trinidad & Tobago Stands

Where are we now? Well, as of 2019, our country is not doing very well in comparison to many other countries; in fact, we rank 90th of 117 countries in the survey. The Open Budget Survey shows us at 30/100 for transparency, 39/100 for budget oversight, and a paltry 7/100 for public participation.

Transparency

How accessible is the information provided to the public? A score of 61 or above means there is enough published material to support informed public debate. T&T scores 30/100 for this measure, so there is much more work to be done.

Budget Oversight

How much oversight do legislatures and auditors have over the budget process? T&T has weak oversight, with a score of 39/100. This is key area for budget reform.

Public Participation

If we want the benefits from transparency, we must be engaged in the budget process. Trinidad and Tobago scores very low here, with a public participation score of 7/100. Going forward, it is imperative that CSOs step up and learn about budget processes so they can help facilitate the changes we need in Trinidad & Tobago.

How CSOs Benefit From Deeper Engagement With the Budget

Increased civic engagement can lead to increased funding, more influential research and better advocacy. By joining together, CSOs help hold government to account and make sure that money that’s in the budget for various purposes gets spent. Believe it or not, sometimes funds are allocated but never get used.

Unspent monies are returned to the consolidated fund. Since ministries attempt to use as much funding as possible, unspent money is seen to reflect a lack of need and, therefore, future allocation to that particular department/ministry may be lower.

This may sometimes lead to funds getting used in a way that is not beneficial. Unfortunately, we’ve had some colossal misallocation of funds in the past. Who can forget the billion-dollar white elephant waste treatment plant? Imagine the good that wasted money could have done.

We need to hold the government to account to ensure that when they make budget decisions they are thinking about the needs of the people of Trinidad and Tobago and allocating money to where it will do the most good.

That’s why it’s important to read and understand the actual budget numbers. If you know where to look, the numbers start to tell a compelling story. They translate into real-life services for actual human beings. Approach your analysis from this perspective so that you don’t lose sight of why you’re doing this in the first place.

It can seem like a lot of work to slog through budget documents and you might think it’s easier to just read the Budget Statement to find out what money has been allocated to the causes you care about. However, there are many documents associated with the annual budget and you may not get all the information you need from the Budget Statement. This is the flashy document that pulls your focus to the government’s priorities and, and while their priorities should be the same as those of CSOs and citizens, this may not always be the case.

Why should you dig deeper into the budget?

It depends on what kind of Civil Society Organisation to which you belong:

- Community group

- Business trade organisation

- Lobby group

- Journalist

- Academic

- Legal expert

How this guide helps

Use this guide to get an overview of the process and gain an understanding of what could be added to make it more robustly transparent. Find out where to find information about where T&T revenue comes from, how public money is allocated and spent, and where to find details about spending in various areas. The next chapter gives an overview of the budget process.

National Budget Process

Government Policies and Priorities

You will find the government's states policies and priorities in the Budget Statement and various Programme documents. Each year the Executive’s budget follows a particular theme. Resetting the Economy for Growth and Innovation is the theme that guides the 2020-2021 budget, so priorities should follow this objective.

What is still needed is a medium-term policy framework that details the manner in which these priorities are to be targeted. We can also draw conclusions about government priorities in sectors like education, health, police, and community development by looking at the budget figures. There is only a certain amount of revenue and borrowed money available to allocate, so trade-offs must be made.

Year over year, where has less money been allocated? Are some programmes getting less money and some getting more? The numbers make policy priorities clear.

A review of all the budget documents shows where money was allocated and whether it was actually deployed. Ideally, the prioritisation of programmes should be based on public engagement before the budget is presented, and that is what we are trying to encourage with this guide.

Mid-year reviews show that at times priorities change, and so the budget may change through the use of supplemental appropriation acts or variation of existing ones. However, there is no law or regulation requiring the executive to obtain approval from the legislature prior to spending excess revenues, and in practice the executive spends these funds before obtaining approval from the legislature.

Budget Stages

The budget goes through four broad stages: drafting, legislative, implementation, and audit. Those are outlined here, along with the steps that must be completed before the process can move on to the next stage.

Drafting Stage

The Minister issues a “call circular” - This is a document that goes to ministers, permanent secretaries, heads of departments and the chief administrator. It sets out requirements for these officials to follow when they prepare their draft budget estimates. It outlines priorities and references.

Proposals submitted - Deadline April 30. Ministries and Departments submit proposals based on their strategic plans and on their Customer Service Delivery Plans.

Examination & consultation - May to mid-Sept. Ministries, departments, and other government agencies justify their proposed expenditures through discussions with the Ministry of Finance. They are mandated to conduct consultations with stakeholders.

- Technical budget hearings

- Executive review

- Consolidation, validation and confirmation

- Presentation to the Minister of Finance

Bill is drafted - The Minister of Finance makes adjustments and submits to Cabinet for approval for specific measures. The Appropriations Bill is drafted.

Legislative Stage

Appropriations Bill presented - Minister of Finance lays and presents the budget and other documents in Parliament

Debate - The Appropriation Bill is debated and passed in the House of Representatives and the Senate

Passage of Appropriation Bill and President's Assent - The Government’s Financial Year starts October 1 and ends on September 30 of the following year. The Appropriation Act for the financial year dictates all government expenditures.

After the bill is passed in the Senate, there are additional steps which must take place before the Bill is forwarded to the President for assent.

- The proof of the Act is sent to the Chief Parliamentary Counsel and the Director of Budgets, Ministry of Finance for review. Any corrections are inserted in the proof.

- The proof of the Act is sent to the Government Printer. Four assent copies are signed by the Clerk of the House and the Clerk of the Senate.

- The Bill file, along with the four signed assent copies, are sent to the Office of the Solicitor General for the Legal Report of the Attorney General to be completed.

- Once the Legal Report of the Attorney General has been prepared, the Office of the Solicitor General forwards the Bill file and the Legal Report for the signature of the Attorney General.

- The Office of the Attorney General and Legal Affairs returns the Bill file to the Office of the Parliament.

- The Office of the Parliament sends the four signed assent copies to the President of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago for assent.

Only when this administrative process is complete can the Minister of Finance sign the General Warrant that authorizes the Comptroller of Accounts to issue monies from the Consolidated Fund to meet the expenditure for the financial year.

Implementation Stage (Disbursements)

- Treasury receives permission to withdraw from Consolidated Fund within the budgetary limits (outlined in the Appropriation Act)

- Ministries & Divisions apply to MOF for funds

- Auditor General sometimes authorizes releases to ensure the amount is within limit of Act

- Accounting Unit (Treasury) then releases funds by granting credit from the Exchequer Account. To ensure transparency and accountability, there are rules for processing, recording and reporting of all spending.

Revenue Collection - Government receives revenue through fiscal (taxation) measures. Revenue collected is paid to the Exchequer Account held at the CBTT.

Audit Stage

Legal procedures have been put in place to prevent mishandling or theft of revenues from the Consolidated Fund. The following are roles responsible for oversight.

Minister of Finance - Responsible for supervising the Fund and directing matters that relate to the financial affairs of the state. Fund withdrawals require MOF authorization.

Auditor General - Conducts audits of all financial accounts of officers, courts, state-owned and controlled enterprises, and all state authorities in T&T. Prepares an annual report for Parliament, the President, and the Minister of Finance and the Economy.

Accounting Officer - Appointed by the Treasury (the Government’s Bank) to ensure that a) expenditures do not exceed the amount authorized by Parliament and b) funds are spent for their intended purposes

Internal Auditor - Reports to the Accounting Officer and reviews accounting operations to ensure that internal control systems are operating efficiently.

Receiver of Revenue - Supervises and ensures that revenues are accounted for and collected on time.

Public Accounts Committee - Examines the audited accounts of Government MInistries and reviews comments by Auditor General. Encourages Heads of Government and Departments to respond to the Auditor General’s advice.

Public Accounts Enterprises Committee - Watches over public sector projects and examines relevant documents to determine if the projects are being managed in accordance with sound business principles and commercial practices.

Revenue & Expenditure

Revenue: How government gets income

In order for governments to function and deliver services to citizens, they must have incoming money, or revenue. This revenue comes from taxes, property holdings, borrowed money, and other sources, and is detailed in budget documents.

Because we are a resource-rich nation, royalties on oil and gas accounts contribute a substantial amount of revenue. Still, the bulk of T&T’s revenue, almost 68%, is derived from taxes.

- Taxes on Income and Profits

- Taxes on Property

- Taxes on Goods and Services

- Taxes on International Trade

- Other Taxes

Non-tax revenue, almost 27%, accounts for the next-largest source. Non-tax revenue includes property income, other non-tax revenue, and repayment of past lending.

Capital Receipts (non-recurring items such as sales of assets) and Financing (borrowing) make up the remainder.

An abstract from page v of "Draft Estimates of Revenue 2021," recreated here, shows that revenue and estimates were revised down for 2020, along with estimates for 2021.

Details of revenue from oil and gas royalties, originally found in "Draft Estimates of Revenue 2021" on page 18 under Head 06 - Property Income

How COVID-19 has affected T&T revenue collection

T&T depends heavily on energy sector tax revenue and the slowed economic activity caused by covid-19 has destroyed demand for oil and gas, lowered commodity prices, and shrunk the country’s energy sector tax base. This means expected shortfall in the billions. (TT$9.2B).

WTI Projections before and after the pandemic

Before - oil price of US$ 60/barrel and natural gas price of US$3.00 per million standard cubic feet (mmbtu)

After - oil price of US$ 25/barrel and natural gas price of US$1.80 per million standard cubic feet (mmbtu)

This is a huge shortfall. To make up the difference, the government announced plans in April 2020 to raise TT$ 6 billion through these means:

- Borrow locally and externally

- Draw on HSF funds

These funds are being used to stimulate economic activity, support businesses and households, and prevent further job loss.

Unlike other countries in the region, T&T has a large pool of savings in its Heritage and Stabilization Fund (HSF) to finance its battle against Covid-19. With a new and unbudgeted spend of TT$ 6 billion on Covid-19 relief, coupled with significantly lower than planned energy revenues, T&T’s anticipated “rainy day” has arrived. The Government plans to withdraw, at most, US$1.5 billion for budgetary support.

Heritage and Stabilisation Fund (HSF)

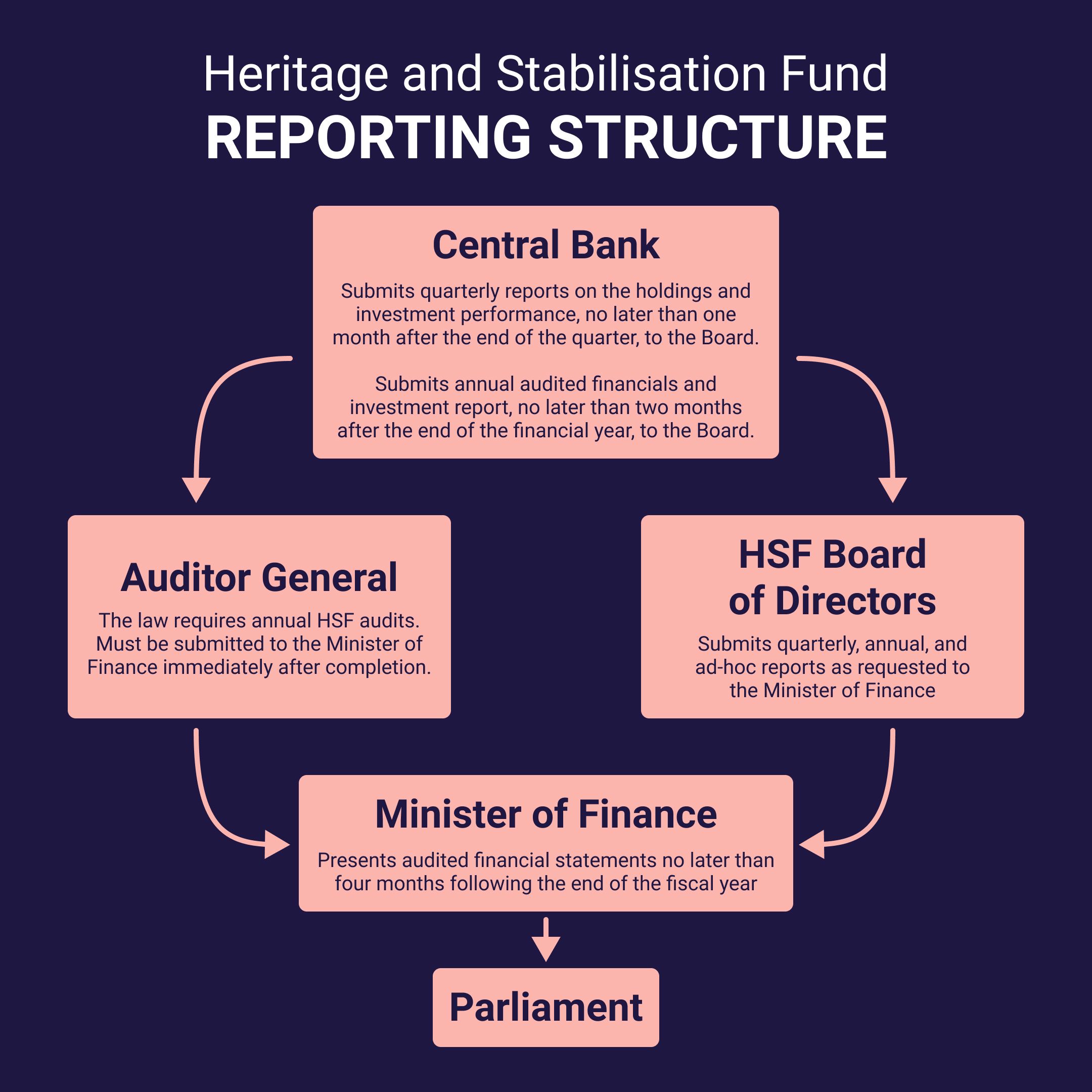

How the HSF works

The purpose of the HSF is to provide budgetary support for the Government in the event that a fall in oil or gas prices/ production cause a sustained shortfall in Government revenues (i.e. stabilization function). The Fund also has a heritage objective, which is to save oil wealth for future generations.

The value of the Fund increases when surplus oil revenues are deposited by the Ministry of Finance. Some of the HSF savings/ monies are also invested in various US and non-US assets that may generate positive returns and add to the value of the Fund. The Fund is governed by strict legal rules of deposits and withdrawals, it is overseen by a Board, and is audited by the Auditor General to prevent any financial mismanagement.

Deposit and Withdrawal Rules

- International oil and gas prices are used to estimate revenues.

- Government can withdraw only if actual petroleum revenues are less than what the government projected by at least 10%.

- 60% of excess petroleum revenues are to be deposited to the Fund within the financial year.

- The amount to be withdrawn can be 60% of the shortfall in revenues but it cannot exceed 25% of the Fund.

Prevention of stealing and corruption

The government must be able to collect all the revenue due to it if it is to serve the country, especially given the situation with Covid-19.

Each year, tax evasion erases millions of dollars of revenue. In 2019, that number was TT$ .7 billion. Obviously, that is unacceptable and in April 2020 attempts to improve the national tax administration system bore fruit when the T&T Revenue Authority Bill, 2018 was passed. With the passing of this Bill, a new institution called the T&T Revenue Authority (TTRA) will replace the BIR and Customs and Excise Division of the Ministry of Finance. The hope is that the TTRA will increase public revenues while reducing tax evasion and make space for further public saving/spending.

The Bill establishes the Authority as a separate legal entity with the responsibility for assessing, collecting, administering, and enforcing of revenue laws, border control and providing revenue collection services to statutory and other public bodies. It also empowers the Auditor General with the ability to independently audit the country’s revenues and highlight any financial irregularities.

Expenditures: How government allocates public money

Since the government has a limited supply of money to spend, where the money is spent tells us a lot about its priorities. The budget is prepared months in advance and is based on assumptions that look at spending in previous years.

Even if the forecast for expenditures is accurate, events often happen that change the outlook and there is a difference between what the government planned to spend and what it actually spends. In 2020 and 2021 COVID-19 has had and will continue to have a big impact.

You can look to revised numbers to see the differences. The estimates of revenue show the actual number from the previous year, the estimate for the current year, the revised estimate for the current year, and finally, the estimate for the coming year.

Royalties on oil and gas projections are based on international market analysis. If prices are high or expected to increase, so would the spending capacity. The opposite would also apply.

The government is only obliged to deposit excess capacity if the resource prices exceed budgeted prices by 10% or more. This can influence how the government chooses the budgeted oil and gas prices.

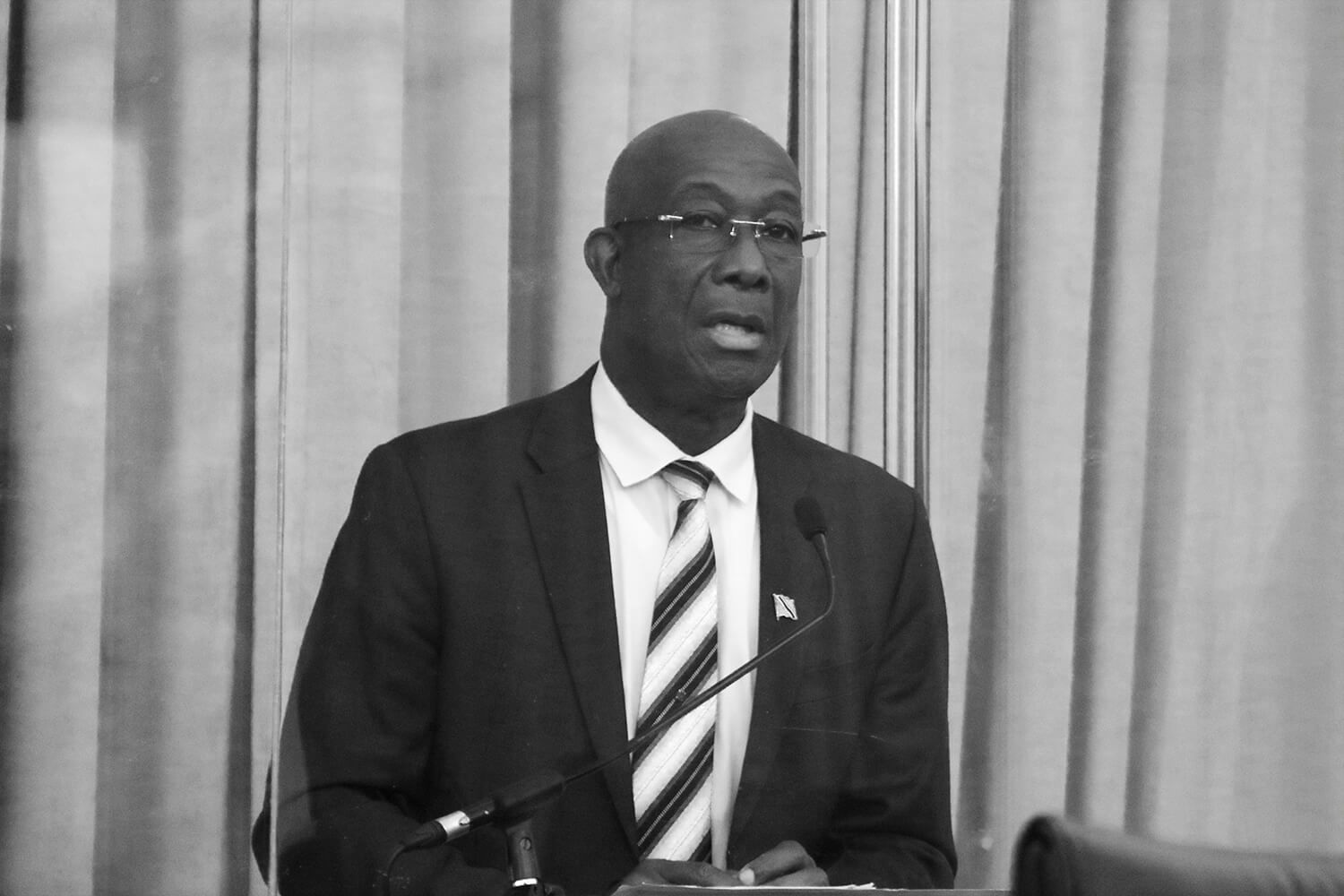

Minister of Finance Colm Imbert presents the 2021 Budget in the House of Representatives on Oct. 5.

Minister of Finance Colm Imbert presents the 2021 Budget in the House of Representatives on Oct. 5.

An Exploration of Important Budget Documents

Budget documents consist of narrative documents and documents with tables of numbers. For a narrative version of budget allocations, start with the Budget Statement. This is where the government puts forth its main priorities. Then, move on to the other narrative documents. Finally, the Draft Estimate documents detail the budget numbers.

Where you should focus your attention depends on your role. For example, if your reason for reading the budget is to get funding, you’ll approach it from a different perspective than if you are looking for information to feed a news story.

You may follow the order discussed here, or start by looking at the numbers and use the narrative documents to answer questions that arise from your analysis. Here are some of the real-life reasons to delve into the budget, depending on your role:

- To prepare a proposal for the following year

- To gain insight and get information for academic research or news stories

- To monitor a particular sector or project

Budget Statement

This is the sweeping, overall messaging about the budget. It lays out priorities and major goals.

Draft Estimates

Draft estimates provide specific detailed numbers on revenues and expenditures. To find narrative information about challenges in implementation and how they are being addressed, look at Social Sector Investment Programme and Public Sector Investment Programme (two separate documents for each of Trinidad and Tobago).

Currently, the only way to track differences between official policy and the budget estimates is to consult the mid-year review. Other documents that would provide that information, such as in-year reports or year-end reports, are not produced and publicly available in Trinidad & Tobago.

CSOs should not only rely upon the Government alone for information, particularly if they are looking for impartial information.

- Draft Estimates of Development Programme

- Draft Estimates of Expenditure

- Draft Estimates of Recurrent Expenditure

- Draft Estimates of Revenue

- Draft Estimates of Revenue and Expenditure of the Statutory Boards and Similar Bodies and of the Tobago House of Assembly

Other Budget Documents

- Public Sector Investment Programme

- Public Sector Investment Programme Tobago

- Review of the Economy

- Social Sector Investment Programme

- State Enterprise Investment Programme

You may also consult some non-government sources of information.

The difference between current and capital accounts and expenditures

You will see the terms below used in the Draft Estimate documents.

The Current Account contains recurring revenue.

The Capital Account contains surplus/deficit, financing, and Capital Revenue (non-recurring items) information.

Current expenditures are what is spent on day-to-day government operations. A capital expenditure generally gives a lasting benefit but does not recur year after year.

For example, building a recreational facility will benefit a community for years. While its construction is a capital expenditure, its day-to-day staff and maintenance is included in current expenditures.

In the draft expenditure documents you’ll see that these types of expenditures are separated.

How budget information is categorised in the tables

Revenue

The "head" is the main classification for each revenue category. It’s then broken down into Sub-head/Receiver/Item/Sub-Item.

Expenditures

The "head" is the main classification for each ministry or department. Sub-heads correspond to categories of spending. For example, Personnel is subhead 01, Goods and Services subhead 02, etc. These expenditure subheads are the same across all ministries and departments, although not every department uses money from every category.

This will be much clearer when you look at the actual budget documents.

How to determine if allocations are in line with government policy and if the numbers are realistic

- Corroborate with Central Bank reports

- Corroborate with other budget documents to see updates of progress based on government policy:

- Public Sector Investment Programme

- Public Sector Investment Programme Tobago

- Social Sector Investment Programme

The numbers are based on Government assumptions, so how realistic they are depends on the accuracy of those assumptions.

You may review some macroeconomic assumptions in the Medium Term Outlook section of the Budget Statement. You’ll find highlighted projections to 2021 including growth in the non-energy sector, the medium term fiscal adjustment, public sector debt, and balance of payments starting on page 28 of the Budget Statement.

Other assumptions are made on the prices of oil and gas, which informs the budgeted revenue for the fiscal year.

Government Policy is not guided by the medium term policy framework. There are no specified performance indicators except those from the Social Sector Investment Programme.

Where to look for your interests (and some examples)

The appendices of the two Public Sector Investment Programme documents, as well as the appendices of the Social Sector Investment Programme are a good starting place to get an idea of how money is being spent on community programmes. Once you’ve found something that interests you, you can then move on to find the matching budget numbers.

Taxes

In the budget statement itself you will find information about various tax matters.

In an effort to stimulate the economy and provide relief to families, the personal income tax exemption limit is increased so that all individuals who earn $7,000 a month or less will be exempt from income tax. Although this will cost in terms of revenue, the government expects that the demand created by putting money back in the hands of consumers will add to GDP in an amount that outweighs the costs.

Tax allowances have increased for corporate sponsorships of creative industries such as fashion, entertainment, and sports.

As part of the COVID-19 relief plan, workers in creative industries will be eligible to receive short-term income relief of $5,000. This applies to the fields of music, film, dance and theatre, heritage, literature publishing, festivals and broadcasting.

Part of the Public Investment Strategy are fiscal incentives in the form of tax breaks. The Public Sector Investment Programme discusses target areas such as: renewable energy, energy efficiency and conservation, the creative industry, growth of SME's, Technology, Manufacturing and Agriculture.

There is a plan for the construction sector to be incentivised by tax relief for approved development projects, including housing and commercial and industrial building.

Coronavirus Spending

A special feature on page 56 of the Social Sector Investment Programme 2020/2021 supplies data on expenditures related to the pandemic.

The Auditor General and various standing committees are responsible for ensuring funds appropriated under pandemic relief measures are spent appropriately.

- Financial Scrutiny Committee

- Public Accounts Committees

- Financial Scrutiny Unit, Parliament of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago conducts budgetary review and analysis for each Head of Expenditure

While it is a good practice to have these Ministries provide summaries of their activities, keep in mind that they are self-reported. The Financial Scrutiny Unit does not conduct its own budget analyses for budget formulation and approval. As a result, legislative and audit oversight tend to be limited and weak in Trinidad and Tobago.

Budget Deficit

You could review various years’ budget statements, but there are also publications and data produced and provided by the Central Bank of Trinidad and Tobago’s Annual Economic Reviews.

T&T’s public account (i.e. the Exchequer Account) has been running a deficit since 2003. This means that we have been spending more than we have received in revenue for all that time. When money is borrowed it must be paid back and the interest on the borrowed money is added to what is owed. Any overdraft balances from previous years are added to the current balance and must be paid.

Expenditure and public debt

How much the government spends (relative to its income), what it spends on, and its ability to repay its loans are important to understand T&T’s fiscal health.

In order to get out of the “overdraft trap” that has been created, Government must invest in activities such as capital and development spending, activities that will facilitate growth. Currently, it spends significantly more on repaying debt and current transfers and subsidies that it does on growth activities.

In fiscal 2019, the country’s debt stood at TT$ 124.4 billion dollars and the Government plans to meet the increased fiscal deficit in 2020 by borrowing further from external and local sources.

While it is common for countries to borrow, can T&T meet its current debt given lower than expected revenue and economic growth projections? What are the risks and the probability that unpredictable negative events can further raise debt to levels beyond the Government’s ability to service/ repay?

Debt Relative to GDP and its Economic Impact

T&T’s debt to GDP ratio of 74.3% (in September 2019) implies that the country’s total debt represents 74% of the income that it generated domestically in fiscal year 2019.

Infrastructure Spending

The Draft Estimates of Development Programme has two sections, the cosolidated fund and the infrastructure development fund.

Summary ix and x detail pre-investment, productive sectors, economic infrastructure, social infrastructure, and multi-sectoral and other services.

Sub-items under the following items that have been detailed: 1) Pre-Investment 2) Productive Sectors 3) Economic Infrastructure 4) Social Infrastructure 5) Multi-Sectoral and Other Services

Under Social Infrastructure for example, sub-headings for which expenditure is detailed include: Defense, Education, Health, Housing etc.

Track increases and decreases in programme allocations

The draft estimates provides data in economic, functional and programme classifications for various years prior to the budgeted year so comparisons can be made. In some instances variances are also explained.

Social Sector Investment Programme (SSIP)

Chapter two provides an overview of the Social Sector and a review of social programmes and initiatives for the previous budgeted year.

Information on transfers and subsidies

The budget presents budgetary information classified according to the nature of the expenditure. The expenditures are disclosed crossed by Head, sub Head, Item and sub Item of expenditure.

The Draft Estimates of Expenditure for the Financial Year 2019 presents expenditure under the sub heads for each administrative unit: 1) Personnel Expenditure 2) Goods and Services 3) Minor Equipment Purchases 4) Current Transfers and Subsidies.

Other than that, spending benefiting specific sectors or activities is usually presented in the Budget Statement as specific subsidies or grants.

Example: Agriculture Programmes

On page 14 of the Budget Statement, you’ll find an overview of Agriculture.

On page 71 of the Social Sector Investment Programme you’ll find an initiative called the Agriculture Incentive Programme.

In "Draft Estimates of Expenditure-PE-2021" on page 314 are the estimates of expenditure for the Ministry of Agriculture, Land and Fisheries.

Then, in the Draft Estimates of Development Programme, on page 160, the expenditures from the Consolidated Fund are detailed for the same ministry.

Money From International Development Agencies

Many CSO projects are funded by subventions and monies from International Development Agencies.

Estimates of some but not all donor assistance is reported.

The Public Sector Investment Programme identifies financing arrangements for projects with funding from multilateral and bilateral external sources, along with explanations.

Draft Estimates of Development Programme identifies loans and grants towards various administrative Heads and ministries. There are no narratives included. In-kind assistance is not indicated.

In the document Public Sector Investment Programme at the end of the document there is a table listing sources of funding, including grants and loans.

In the document Public Sector Investment Programme Tobago at the end there is a detailed table of funds provided under grants/programmes by international cooperation BUT once again not ALL sources are reported such as In-Kind Assistance.

What Comes Next

Suggested Improvements for Trinidad and Tobago

We need to improve budget transparency and better hold government to account. As with anything worth doing, it will take hard work and time. The first step is education and a demonstration by CSOs and citizens that they have a will for civic engagement. We are not at the point yet where there is a designated portion of the T&T budget available for the participatory budgeting process discussed next, but there is an opportunity for Civil Society Organizations to submit proposals and work together to push for some of the actions outlined below.

The case for participatory budgeting

Participatory budgeting started in Brazil in the late eighties as an anti-poverty solution. Basically, the government sets aside a portion of the budget and community members decide how the money is spent. The key to this process is outreach, to find those in the community who have valuable input but who usually don’t participate.

This is powerful because it’s real money being put to work where it’s actually needed, and the people deciding what is needed are the people who will benefit. Government officials sometimes have gaps in knowledge about communities and that can result in poor decisions about where to spend money.

Countries around the world have seen previously marginalized and disenfranchised citizens get the opportunity to have their voices heard by government. Often, the participatory budget process results in the emergence of new leaders and the strengthening of democracy on a local level.

We are not yet at that point, but we are working to get there, and CSOs are extremely important to the transition.

Why CSOs are important to open budgeting

Civil Society Organisations can:

- Share critical information about their community’s needs, which leads to stronger policy choices when taken into account by government

- Summarise and provide budget information to their community

- Provide opinions on how to implement proposals

- Develop allies in government agencies

CSOs should team up with donors

Medium and long-term development strategies such as Vision 2030 and updates on progress will provide some information but donors, particularly international donors, should team up with CSO’s to demand greater accountability.

Here are some changes to push for

More public input

One challenge for public entities in reviewing the budget documents in detail prior to its enactment is the fact that they are only made available on budget day itself, usually after the budget has been presented by the Minister of Finance. Because of this, the budget is hardly ever modified from its proposal form. There is not enough time to raise questions from the date of proposal to the date of enactment.

To improve this process, the timing and information relevant to the budget should be made available ahead of time and the government should report on how public participation was engaged, and how it informed budget priorities.

Trinidad and Tobago's Ministry of Finance has established council during budget formulation but, to further strengthen public participation in the budget process, should also prioritize the following actions:

- Pilot mechanisms to monitor budget implementation.

- Expand mechanisms during budget formulation that engage any civil society organization or member of the public who wishes to participate.

- Actively engage with vulnerable and underrepresented communities, directly or through civil society organizations representing them.

Trinidad and Tobago's Parliament has established public hearings related to the approval of the annual budget and public hearings related to the review of the Audit Report, but should also prioritise the ability of any member of the public or any civil society organisation to testify during hearings on the budget proposal prior to its approval.

Audit practice

Trinidad and Tobago's Office of the Auditor General should establish formal mechanisms for the public to assist in developing its audit program and to contribute to relevant audit investigations. We need to identify metrics to evaluate the effectiveness of the budget.

Any member of the public or any civil society organisation should be allowed to testify during hearings on the Audit Report.

We should improve the comprehensiveness of the Audit Report and Enacted Budget.

Local Government reform

There is a lot that can be done at the local level to overcome political interference and manipulation, inadequate funding, and a sluggish administrative structure. The current legislation for municipalities is inadequate, but The Ministry of Rural Development and Local Government is working with Local Government to create a more modern Local Government system.

Within the Government’s policy for Local Government Reform there are some areas of responsibility presently under the jurisdiction of Local Government that will be given additional responsibilities.

Here are some key reforms under consideration:

- Corporate Restructuring of the Ministry of Local Government and Municipal Corporations

- Human Resource Development and Institutional Restructuring

- Local Area Regional Planning and Development

- Information and Communications Technology (ICT) and Communications

- Waste Resource Management

- Disaster Preparedness and Management

- Municipal/Community Policing

- The development and establishment of standards and monitoring and evaluation mechanisms

Produce and publish more information for accountability

Include in the Executive's Budget Proposal more comprehensive financial and macroeconomic information.

Produce and publish the following reports online:

A Pre-budget Statement sets out a government’s budget strategies for the coming year, if not for an additional two years beyond. In some countries it is provided only to the government’s cabinet, but ideally it should be made available to the legislature and the public as well. This document would serve to encourage debate before the budget is drafted to create expectations of what it may include and improve the budget formulation process within the government. It also provides a way for the public to understand the link between policies and budget allocations.

A Citizens Budget is a short, nontechnical version of the budget. The annual budget, with its detailed supporting documents, can be difficult and time consuming even for experts. In order to help the public make sense of the budget, and thereby make it more accessible, it is essential that governments issue a report such as this.

In-Year Reports provide snapshots of how the budget is being implemented during the budget year. They are periodic reports that list major components of the budget. They attempt to provide a measure of the trends in revenues and expenditures to date and they may provide explanations for any significant changes between estimated and actual spending. This is important for budget transparency because they require the government to put in place the systems and knowledge to track this aggregate data. This also promotes accuracy and availability of budget data. When it is time to create the Mid-Year Review, the document we discuss next, In-Year Report information can help clarify if there is a need for spending adjustments.

The Mid-Year Review is provided about halfway through the budget year as an assessment of fiscal performance against the enacted budget. Is the budget coping with current macroeconomic developments? Are revenue collections keeping up as expected? Have the prices of natural resources undergone substantial change? Should adjustments be made to spending in various departments or sectors?

The Year-end Report, different from the Audit Report (which is prepared by an external agency that is independent of the executive branch and is a detailed statement of government’s actual expenditures and revenue by budget category), presents the performance of the budget compared to the original budget. It shows what was actually spent and collected in comparison to what was budgeted. Did the budget reach its policy objectives, both on a macro level and for specific programs?

Concrete steps CSO representatives can take

- Learn how the budget works. You must understand how the process if you are to participate. Take action now by checking out this pre-recorded webinar.

- Get in on the process. Draft a proposal and/or participate in public policy discussions.

- Get organised. Speak with other CSOs to see how you can work together to pressure the Minister of Finance and try to get more meetings and consultation from the government well before the next call circular is issued.

- Call for the window for proposal submissions to expand.

- Push for specific measures. For example, engage with government in an effort to produce a social spending report out of the Ministry of Social Development. This could have a major effect on social development spending in the budget.

- Speak with officials to find out more about local government reform and how regional allocations are made and spent.

What’s next?

Trinidad and Tobago has the opportunity to embrace a future that includes participatory budgeting, and with the help of civil society organisations we will get there. The issue is how we can make it work. That’s what we will explore next.

Updated: February 1, 2021